Pakistan - History

The ruins of ancient civilizations at Mohenjodaro and at Harappa in the southern Indus Valley testify to the existence of an advanced urban civilization that flourished in what is now Pakistan in the second half of the third millennium BC during the same period as the major riverain civilizations in Mesopotamia and Persia. Although overwhelmed from 1500 BC onward by

large migrations of nomadic Indo-European-speaking Aryans from the Caucasus region, vestiges of this civilization continue to exist in the traditional Indic culture that evolved from interaction of the Aryans and successive invaders in the years following. Among the latter were Persians in 500 BC , Greeks under Alexander the Great in 326 BC , and—after AD 800—Arabs, Afghans, Turks, Persians, Mongols (Mughals), and Europeans, the last of whom first arrived, uniquely, by sea beginning in AD 1601.

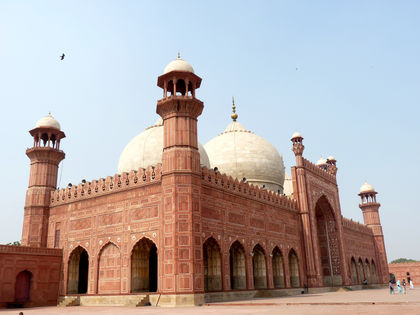

Islam, the dominant cultural influence in Pakistan, arrived with Arab traders in the 8th century AD . Successive overland waves of Muslims followed, culminating in the ascendancy of the Mughals in most of the subcontinent. Led initially by Babur, a grandson of Genghis Khan, the Mughal empire flourished in the 16th and 17th centuries and remained in nominal control until well after the British East India Company came to dominate the region in the early 18th century. Effective British governance of the areas that now make up Pakistan was not consolidated until well into the second half of the 19th century.

In 1909 and 1919, while the British moved gradually and successfully to expand local self-rule, British power was increasingly challenged by the rise of indigenous mass movements advocating a faster pace. The Indian National Congress, founded in 1885 as little more than an Anglophile society, began to attract wide support in this century—especially after 1920—with its advocacy of nonviolent struggle. But because its leadership style appeared to many Muslims to be uniquely Hindu, Muslims formed the All-India Muslim League to look after their interests. National and provincial elections held under the Government of India Act of 1935 confirmed many Muslims in this view by showing the power the majority Hindu population could wield at the ballot box.

Sentiment among Muslims began to coalesce around the "two-nation" theory propounded by the poet Iqbal, which declared that Muslims and Hindus were separate nations and that Muslims required creation of an independent Islamic state for their protection and fulfillment. A prominent Bombay (now Mumbai) attorney, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who came to be known "Quaid-i-Azam" (Great Leader), led the fight—formally endorsed by the Muslim League at Lahore in 1940—for a separate Muslim state to be known as Pakistan.

Despite arrests and setbacks during the Second World War, Jinnah's quest succeeded on 14 August 1947 when British India was divided into the two self-governing dominions of India and Pakistan, the latter created by combining contiguous, Muslim-majority districts in British India, the former consisting of the remainder. Partition occasioned a mass movement of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs who found themselves on the "wrong" side of new international boundaries; more than 20 million people moved, and up to three million of these were killed.

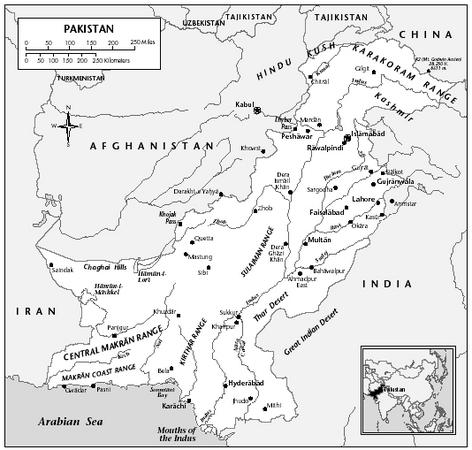

The new Pakistan was a state divided into two wings, East Pakistan (with 42 million people crowded mainly into what had been the eastern half of Bengal province) and West Pakistan (with 34 million in a much larger territory that included the provinces of Baluchistan, Sind, the Northwest Frontier, and western Punjab). In between, the wings were separated by 1600 km (1000 miles) of an independent, mainly Hindu, India professing secularism for its large Muslim, Christian, and Sikh minorities.

From the capital in Karāchi, in West Pakistan, the leaders of the new state labored mightily to overcome the economic dislocations of Partition, which cut across all previous former economic linkages, while attempting to establish a viable parliamentary government with broad acceptance in both wings. Jinnah's death in 1948 and the assassination in 1951 of Liaquat Ali Khan, its first prime minister, were major setbacks, and political stability proved elusive, with frequent recourse to proclamations of martial law and states of emergency in the years following 1954.

Complicating their task were the security concerns that Pakistan's new leaders had regarding India in the aftermath of the bitterness of partition and the dispute over Jammu and Kashmir. In the early 1950s, they sought security in relationships external to the subcontinent, with the Islamic world and with the United States, joining in such American-sponsored alliances as the Baghdad Pact (later—without Baghdad—the Central Treaty Organization or CENTO) and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). They received extensive American economic and security assistance.

In the years leading up to 1971, the domestic political process in Pakistan was dominated by efforts to bridge the profound political and ethnic gap that—more than geography—separated the east and west wings despite their anxiety about India and shared commitment to Islam. Economically more important, the Bengali east wing, governed as a single province, chafed under national policies laid down in a west wing dominated by Punjabis and recent refugees from northern and western India. Seeking greater autonomy, voters in East Pakistan voted the Muslim League (ML) out of office as early as 1954, resulting in a period of direct rule from Kara¯chi. In 1958, the Army chief, Gen. Muhammad Ayub Khan, seized control of Pakistan, imposing martial law and banning all political activity for several years. Ayub later dissolved provincial boundaries in the west wing, converting it to "one unit," to balance East Pakistan. Each "unit" had a single provincial government and equal strength in an indirectly elected national legislature; the effect was to deny East Pakistan its population advantage, as well as its ability, as the largest province, to play provincial politics in the west wing.

Ayub's efforts failed to establish stability or satisfy the demands for restoration of parliamentary democracy. Weakened by his abortive military adventure against India in September 1965 and amid rising political strife in both wings in 1968, Ayub was eventually forced from office. General Muhammad Yayha Khan, also opposed to greater autonomy for the east wing, assumed the presidency in 1969. Again martial law was imposed and political activity suspended.

Yahya's attempt to restore popular government in the general elections of 1970 failed when the popular verdict supported those calling for greater autonomy for East Pakistan, even in the national assembly. The results were set aside, and civil unrest in the east wing rapidly spread to become civil war. India, with more than a million refugees pouring into its West Bengal state, joined in the conflict in support of the rebellion in November 1971, tipping the balance in Bengali favor and facilitating the creation of Bangladesh from the ruins in early 1972.

Bhutto and his successors

The defeat led to the resignation on 20 December 1971 of Yahya Khan and brought to the presidency Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, whose populist Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) had won a majority of seats in the west wing. A longtime minister under Ayub Khan, the experienced Bhutto quickly charted an independent course for West Pakistan, which became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. He distanced Pakistan from former close ties with the United States and the west, seeking security from India by a much more active role in the Third World and especially in the growing international Islamic movement fueled by petrodollars.

At the polls, the PPP was opposed by the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA), a nine-party coalition of all other major parties including the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI) on the Islamic right, the National Democratic Party on the secular left, the Pakistan Muslim League (PML/Pagaro) in the center, Asghar Khan's Tehrik Istiqlal (TI) on the secular right, and others. Although the results gave the PPP a two-thirds majority in parliament, allegations of widespread fraud and rigging undercut its credibility. PNA leaders demanded new elections, and Bhutto's exercise of emergency powers to arrest them led to widespread civil strife. On 5 July 1977, the army intervened, with the support of the civil and uniformed services and tacit acceptance of the PNA leaders. In ousting Bhutto, army chief General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq partially suspended the 1973 constitution, imposed martial law, and assumed the post of Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA). As calm returned to Pakistan, Zia promised elections for October 1977, but for the first of many times to come, he reversed himself before the event, arguing that he needed more time to set matters aright. And as the months passed, he began to assume more of the trappings of power, creating a cabinet-like Council of Advisers of made up of serving military officers and senior civil servants, chief among whom was longtime Defense Secretary, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, who became Finance Advisor and Zia's strong right arm. His political base broadened by his promises of "clothing, food, and housing" to the rural and urban poor, Bhutto launched limited land reform, nationalized banks and industries, and obtained support among all parties for a new constitution promulgated in 1973, restoring a strong prime ministership, which position he then stepped down to fill. In the years following, Bhutto grew more powerful, more capricious, and autocratic. His regime became increasingly dependent on harassment and imprisonment of foes and his popular support seriously eroded by the time he called for elections in March 1977. His PPP had lost many of its supporters, and he came to rely increasingly on discredited former PML members for support.

In mid-1978, Zia brought Bhutto to trial for conspiracy to murder a political rival in which the rival's father was killed. He also expanded his "cabinet" with the addition of several PNA leaders as advisors, and, when the incumbent resigned, he assumed the added responsibilities (and title) of president. He allowed a return of limited political activity but put off elections scheduled for fall when he was unable to get agreement among the PNA parties on ground rules that would keep the PPP from returning to power.

Bhutto's conspiracy conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court in March 1979, and he was hanged on 4 April. In the fall, and with the PNA now in disarray, Zia again scheduled, then postponed elections and restricted political activity. But he did hold "non-party" polling for district and municipal councils, only to find at year's end confirmation of his concerns about PPP strength when PPP members, identifying themselves as "Friends of the People," showed continuing appeal among the electorate.

Opposition to martial law began slowly to coalesce in 1980 when most of the PNA leadership joined with PPP leaders Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi and Nusrat Bhutto, Zulfikar's widow, to form the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and to demand Zia's resignation and the restoration of the 1973 constitution. But Zia, benefiting from excellent monsoons and from Ishaq Khan's sound economic policies, proceeded by a series measures to expand the role of Islamic values and institutions in society. The public mood stayed quiescent, encouraged by Zia's regular reminders of the turmoil his predecessors had created.

Meanwhile, in neighboring Afghanistan, following a communist coup in 1978 and a Soviet invasion in 1979, Zia assumed a strong anticommunist leadership role, rallying the Islamic world and the UN. He resurrected close ties with the United States to enhance Pakistan's security and in the 1980s signed US $3.2 and US $4.02 billion economic and security assistance agreements with the United States. He also improved relations—normally parlous—with India with normalization in trade, transport, and other non-sensitive areas. Nonetheless, Pakistan's anxiety about the much more powerful India on its borders remained high in the absence of a solution of the dispute with India over the status of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

The Kashmir dispute cuts to the heart of the "two-nation" theory and as such is part of the unresolved legacy of the 1947 partition of British India which did not address the future of the over 500 princely states with which the British Crown had treaty ties. Most chose one or the other dominion on grounds of geography, but Kashmir bordered both new nations and thus had a real option. A Muslim-majority state, with a Hindu ruler, Kashmir opted first for neither but then chose to join the Indian Union when invaded by tribesmen from Pakistan. Open warfare ensued in Kashmir between Indian and Pakistani troops in 1948– 49 and brought the dispute to the fledgling United Nations.

A UN cease-fire left a third of Kashmir under Pakistani control and the remainder, including the Vale of Kashmir, under Indian control. A 1949 agreement to hold an impartial plebiscite broke down when the protagonists could not agree on the conditions under which it would be held. Pakistan today administers its part—Azad (free) Kashmir—legally separate from the rest of Pakistan; Indian Kashmir is a state in the Indian Union, which has held stateside elections but no plebiscite.

The Kashmir issue has defied all efforts at resolution, including two additional spasms of warfare in 1965 and 1971, and subsequent Indo-Pakistan summits at Tashkent (1966) and Simla (1972). In the late 1980s, India's cancellation of election results and the dismissal of the state government led to the beginning of an armed insurrection against Indian rule by Kashmiri Muslim militants. Indian repression and Pakistan's support of the militants has threatened to spark new Indo-Pakistan conflict and keeps the issue festering.

In Pakistan in 1984, President Zia held a referendum on his Islamization policies in December and promised that he would serve a specified term of five years as president if the voters endorsed his policies. The MRD opposed him but did not prevent what Zia claimed was a 63% turnout, with 90% in his favor. On the strength of this disputed showing, Zia announced national and provincial elections, on a non-party basis, for February 1985. The MRD again boycotted, but the JI and part of the Pakistan Muslim League (PML) supported Zia. Deemed reasonably fair by most observers, the elections gave him a majority in the reconstituted National Assembly and left the opposition in further disarray.

Ten months later, on 30 December 1985, Zia ended martial law, as well as the state of emergency he had inherited from Zulfikar Bhutto, turning over day-to-day administration to the PML's Mohammad Khan Junejo, whom he had appointed prime minister in March. He also restored the 1973 constitution but not before amending it to strengthen presidential powers vis-a-vis the prime minister. As the Eighth Amendment to the constitution, these changes were approved by the National Assembly in October 1985. They remain a contentious issue today, having subsequently played a key role in institutional tension between incumbents of the presidency and the prime ministership. In the first such instance, frictions developed slowly through 1987, but on 29 May 1988, Zia suddenly fired Junejo, alleging corruption and a lack of support for his policies on Islamization and on Afghanistan. He called for new elections in November, and in June he proclaimed the Shari'ah (Islamic law) supreme in Pakistan.

However, Zia was among 18 officials (including the American Ambassador) killed in the crash of a Pakistan Air Force plane two months later, leading to the succession to power of the Chairman of the Senate, Ghulam Ishaq Khan. As acting president, Ghulam Ishaq scheduled elections for November 1988 in which the PPP emerged with a strong plurality in the National Assembly. Benazir Bhutto, Zulfikar's daughter, who had returned from exile abroad in April 1986, became prime minister with a thin majority made up of her party members and independents. With her support Pakistan's electoral college chose Ghulam Ishaq President of Pakistan in his own right on 12 December 1988.

On 20 August 1990, with Bhutto and Ghulam Ishaq in a growing constitutional struggle over their respective powers, the president, with the support of the army chief, used his Eighth Amendment powers to oust her, alleging corruption, illegal acts, and nepotism. Declaring a state of emergency, he dissolved the National Assembly, named Ghulam Mustafa Jatoi (then leader of the opposition) prime minister, and called for new elections on 24 October. The Punjab high court upheld the constitutionality of his actions, and on 24 October, the voters gave a near-majority to the Islamic Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI), a multi-party coalition resting mainly on a partnership of the PML and the JI. Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, PML leader and former chief minister of Punjab, became prime minister on 6 November and quickly ended the state of emergency.

During late 1992 and early 1993, the president and the new prime minister moved toward a new confrontation over the exercise of their respective powers. Challenged by Nawaz Sharif on the president's choice of a new army chief, Ghulam Ishaq again used his eighth amendment powers to dismiss the government and dissolve the assembly on 18 April, alleging mismanagement and corruption. But public reaction to the president's actions was strong, and on 26 May, a supreme court ruling restored Nawaz Sharif to power, creating a period of constitutional gridlock until 18 July when the army chief brokered a deal in which both Ghulam Ishaq and Nawaz Sharif left office. Sharif resigned and was replaced by Ishaq Khan as interim prime minister by Moeen Qureshi, a former World Bank vice president; the president was then replaced by Wasim Sajjad, chairman of the senate.

Under Qureshi, Pakistan entered a period of fast-paced nonpartisan rule and reform in which widespread corruption was exposed, corrupt officials dismissed, and political reforms undertaken. In his actions, Qureshi was strengthened by public support and his disavowal of interest in remaining in power. He held elections as promised on 19 October, and the PPP, leading a coalition called the People's Democratic Alliance (PDA), was returned to power, with Benazir Bhutto again prime minister, this time with a thin majority. On 13 November, with her support, longtime PPP stalwart Farooq Leghari was elected president. Three years later in 1996, Leghari dismissed Bhutto and her cabinet and dissolved the National Assembly. Bhutto challenged her dismissal and the dissolution of the National Assembly in the Supreme Court. In a 6–1 ruling, the Court upheld the president's actions and found her ousted government corrupt.

Nawaz Sharif won the general election held in February 1997 with one of the largest democratic mandates in Pakistan's history. He immediately set about consolidating his hold on power by repealing major elements of the 1985 Eighth Constitutional Amendment. This transferred sweeping executive powers from the president to the prime minister. Within the next few months Nawaz Sharif dismissed his Chief of Naval Staff, arrested and imprisoned Benazir Bhutto's husband for ordering the killing of a political opponent, and froze the Bhutto family's assets. In March 1998, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Benazir Bhutto (who was abroad at the time) on charges of misuse of power during her tenure as prime minister.

The early months of 1998 were marked by increasing civil disorder in Pakistan, with sectarian killings, terrorist bombings, and violent demonstrations against a controversial Islamic blasphemy law. In January 1999, Nawaz Sharif himself escaped an apparent assassination attempt when a bomb exploded near his residence in the Punjab.

Despite increasing political opposition and a deteriorating economic situation, Nawaz Sharif's popularity received a temporary boost when Pakistan successfully tested five nuclear devices on 28 May and 30 May 1998. This was in response to India's nuclear tests earlier in the month and raised international concerns over a potential nuclear confrontation between Pakistan and India. Tensions eased when Nawaz Sharif and India's prime minister, Atal Behari Vajpayee, signed the historic "Lahore Declaration" on 21 February 1999, committing their countries to a peaceful solution of their problems.

In May 1999, however, several hundred Pakistani troops and Islamic militants infiltrated the Indian-held Kargil region of Kashmir. Two months of intense fighting brought Pakistan and India to the brink of all-out war. Under intense diplomatic pressure from the United States, but against the wishes of Pakistan's military, Nawaz Sharif ordered a withdrawal from Kargil in July 1999. This unpopular decision, plus the widely held view that Sharif' was preparing to impose one-man dictatorial rule in the name of Islam, contributed to the prime minister's eventual downfall.

Distrustful of his army chief of staff, General Pervez Musharraf, Nawaz Sharif dismissed Musharraf on 12 October 1999 while he was in the air returning from a visit to Sri Lanka. However, when the general's plane was denied permission to land at Kara¯chi Airport, army troops loyal to Musharraf seized the airport, arrested Sharif, and returned Pakistan to military rule for the fourth time in the country's short history.

General Musharraf did not impose full martial law. Instead, he declared a state of emergency, suspended the constitution and assumed power as chief executive. Many Pakistanis welcomed the military takeover as a change from the corruption and abuses of Nawaz Sharif's rule. Musharraf introduced modest economic reforms (mostly in the area of revenue collection), restricted the activities of Islamic extremists, and instituted policies to curb lawlessness and sectarian violence. On 23 March 2000, Musharraf announced local elections to be held over a period of seven months between December 2000–July 2001. Significantly, however, no mention was made of national elections or a return to civilian rule. Moreover, the independence of the judiciary was seriously compromised in January 2000, when Musharraf required all judges to take an oath of loyalty to his regime. Nawaz Sharif was tried and found guilty of hijacking and terrorism for trying to prevent Musharraf's plane, a commercial flight with civilians on board, from landing at Kara¯chi in October 1999. Sharif was sentenced on 16 April 2000 to life in prison. In December he went into exile in Sa'udi Arabia after being pardoned by military authorities.

On 20 June 2001 General Musharraf named himself president of Pakistan while remaining head of the army.

After 11 September 2001, US-Pakistani relations were transformed. Prior to the 11 September terrorist attacks on the United States, US policy toward Pakistan was restrained, stressing the need for Pakistan to curtail acts of terrorism, and a need for better Pakistani relations with India. After 11 September, Musharraf supported the US-led bombing campaign in Afghanistan and ties between the two countries were greatly strengthened. The United States removed some sanctions imposed on Pakistan after its 1998 nuclear tests, but retained others imposed after Musharraf's coup. After the Taliban were removed from power in Afghanistan in late 2001, the United States moved to strengthen counterterrorism operations in Pakistan, and to prevent al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters from regrouping in Pakistan (Pakistan shares a 1,510-mile porous border with Afghanistan). In addition, Islamic extremists from Pakistan crossed over into Afghanistan to fight against the US-led coalition.

Relations with India were seriously strained throughout 2002 and into 2003. On 13 December 2001, the Indian Parliament was attacked by 5 suicide fighters, and India blamed the attack on two Pakistan-based Islamic organizations, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad, accusing Pakistan of supporting the groups and giving their leaders sanctuary. Tensions between the two countries flared, and they began to amass hundreds of thousands of troops along their shared border. Pakistan banned Jaish-e-Muhammad and Lashkar-e-Taiba, although it claimed India had not provided evidence of the groups' involvement in the attack. In January 2002, India successfully test-fired the Agni, a nuclear-capable ballistic missile. In May, Pakistan test-fired three medium-range surface-to-surface Ghauri missiles, which are capable of carrying nuclear warheads. President Musharraf stated Pakistan did not want to engage in war, although the country would be prepared to respond with full force if attacked. The standoff between India and Pakistan continued for 10 months— close to one million troops were stationed on the India-Pakistan border, the largest military build-up since the 1971 war. Most of the troops were withdrawn by October 2002, but tensions remained. In December, three Indian men were sentenced to death for aiding in the planning of the assault on Parliament. Relations between India and Pakistan worsened once again at the end of January 2003, with each nation expelling diplomats from the other, accusing them of spying. Throughout 2002 and into 2003, the two countries continued to test-fire ballistic missiles capable of carrying nuclear weapons.

During 2002, Pakistan was home to a series of violent acts directed at Western or Christian targets. In January 2002, Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl was abducted in Karachi, and was later brutally murdered. In March, a grenade attack on a church in Islamabad killed five people, including two US citizens. In May, 14 people were killed in a suicide attack on a bus in Kara¯chi, including 11 French engineers. In June, 12 people were killed in a suicide attack on the US consulate in Karachi. In August, a Christian school north of Islamabad was attacked by gunmen, leaving 6 people dead. In September, 7 employees of a Christian charity in Karachi were murdered, marking the eighth high-profile attack on Christian or Western targets in Pakistan since General Musharraf began to support the US-led campaign against terrorism begun in September 2001.

In April 2002, Pakistan's military regime held a referendum on General Musharraf's presidency; 98% of the votes cast were in favor of Musharraf, giving him another 5-year term as president. In August, he unilaterally implemented 29 amendments to the constitution to grant himself the power to dissolve parliament and to remove the prime minister. He also gave the military a formal role in governing the country for the first time by setting up a National Security Council that would oversee the performance of parliament, the prime minister, and his or her government. Parliamentary elections were held on 10 October, with Quaid-e-Azam, a political faction of the Muslim League supportive of Musharraf, taking the most seats.

In October 2002, the United States confronted North Korea with evidence of its program to build nuclear weapons using enriched uranium. In November, the United States warned Pakistan not to engage in nuclear transactions with North Korea, stating it had evidence Pakistan continued to receive missile parts from North Korea possibly in exchange for nuclear plans and materials, including gas centrifuges needed to create weapons-grade enriched uranium.

On 19 March 2003, the US-led coalition launched war in Iraq. The war has been seen to have set a precedent for authorizing pre-emptive strikes on hostile states. The notion that India and Pakistan might adopt such a policy toward one another has caused international concern. In April 2003, spokesmen from both India and Pakistan asserted that the grounds on which the US-led coalition attacked Iraq also existed in each other's country.