Colombia - History

Archaeological studies indicate that Colombia was inhabited by various Amerindian groups as early as 11,000 BC . Prominent among the pre-Columbian cultures were the highland Chibchas, a sedentary agricultural people located in the eastern chain of the Andes.

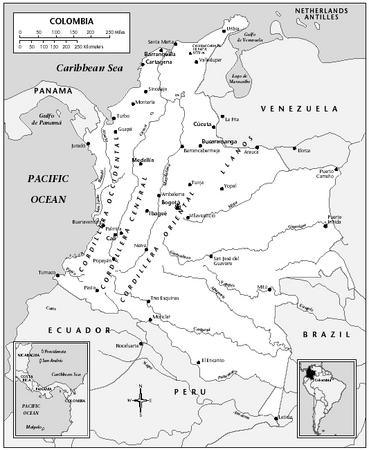

The first Spanish settlement, Santa Marta on the Caribbean coast, dates from 1525. In 1536, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and a company of 900 men traveled up the Magdalena River in search of the legendary land of El Dorado. They entered the heart of Chibcha territory in 1538, conquered the inhabitants, and established Bogotá. As a colony, Colombia, then called New Granada, was ruled from Lima, Peru, until it was made a

viceroyalty. The viceroyalty of New Granada, consolidated in 1740, incorporated modern Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, and Ecuador. The area became Spain's chief source of gold and was exploited for emeralds and tobacco.

In the late 1700s, a separatist movement developed, stemming from arbitrary taxation and the political and commercial restrictions placed on American-born colonists. Among the Bogotá revolutionaries was Antonio Nariño, who had been jailed for printing a translation of the French Assembly's Declaration of the Rights of Man. Independence, declared on 20 July 1810, was not assured until 7 August 1819, when the Battle of Boyacá was won by Simón Bolívar's troops. After this decisive victory, Bolívar was tumultuously acclaimed "Liberator" and given money and men to overthrow the viceroyalty completely.

After 1819 Bolívar's Republic of Gran Colombia included Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. Venezuela and Ecuador seceded, but Panama remained part of Colombia. In 1831 the country became the State of New Granada. Political and financial order was attained under Francisco de Paula Santander, Bolívar's vice president, who took office in 1832. During Santander's four-year term and in the subsequent decade there was intense disagreement over the relative amount of power to be granted to the central and state governments and over the amount of power and freedom to be given the Roman Catholic Church. Characterized by Bolívar as Colombia's "man of laws," Santander directed the course of the nation toward democracy and sound, orderly government.

By 1845, the supporters of strong central government had organized and become known as the Conservatives, while the federalists had assumed the Liberal label. The respective doctrines of the two parties throughout their history have differed on two basic points: the importance of the central governing body and the relationship that should exist between church and state. Conservatism has characteristically stood for highly centralized government and the perpetuation of traditional class and clerical privileges, and it long opposed the extension of voting rights. The Liberals have stressed states' rights, universal suffrage, and the complete separation of church and state. The periods during which the Liberals were in power (1849–57, 1861–80) were characterized by frequent insurrections and civil wars and by a policy of government decentralization and strong anticlericalism.

As effective ruler of the nation for nearly 15 years (1880–94), the Conservative Rafael Núñez, a poet and intellectual, restored centralized government and the power of the church. During his tenure as president, the republican constitution of 1886 was adopted, under which the State of New Granada formally became the Republic of Colombia. A civil war known as the War of a Thousand Days (1899–1902) resulted in more than 100,000 deaths, and the national feeling of demoralization and humiliation was intensified by the loss of Panama in 1903. After refusing to ratify without amendments a treaty leasing a zone across the Isthmus of Panama to the United States, Colombia lost the territory by virtue of a US-supported revolt that created the Republic of Panama. Colombia did not recognize Panama's independence until 1914, in exchange for rights in the Canal Zone and an indemnity from the US.

Conservative presidents held power between 1909 and 1930, and Liberals from 1930 to 1942. During World War II, which Colombia entered on the side of the Allies, social and political divisions within the country intensified.

The postwar period was marked by growing social unrest and riots in the capital and in the countryside. Politics became much more violent, especially after the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, the leftist Liberal mayor of Bogotá. This extended and bloody period of rural disorder (La Violencia) claimed 150,000 to 200,000 lives between 1947 and 1958. Sporadic guerrilla fighting between Liberals and Conservatives, few of whom understood any ideological implications of their loyalty, ripped Colombia apart. La Violencia convinced Colombia's elite that there was a need to bring the rivalry between Liberal and Conservative under control.

The political system in the 1950s had become irrelevant in the midst of the violence. Three years of Conservative government were followed by a populist military government under Gen. Gustavo Rojas Pinilla. Rojas ruled as an absolute dictator, but could not quell the violence still raging in the field. Overthrown largely by a coalition of Conservatives and Liberals that used newsprint as its weapon, Rojas gave up power in May 1957 to a military junta, which promised and provided free elections.

When the fall of Rojas was imminent, Liberal and Conservative leaders met to discuss Colombia's future. Determined to end the violence and initiate a democratic system, the parties entered into a pact establishing a coalition government between the two parties for 16 years. This arrangement, called the National Front, was ratified by a plebiscite in December 1957. Under the terms of this agreement, a free election would be held in 1958. The parties would then alternate in power for four-year terms until 1974. Thus, Liberals and Conservatives would take turns in the presidency. Parties were also guaranteed equal numbers of posts in the cabinet and in the national and departmental legislatures.

In 1958, the first election under the National Front was won by Liberal Alberto Lleras Camargo. As provided in the agreement, he was succeeded in 1962 by a Conservative, National Front candidate Guillermo León Valencia. In May 1966, Colombia held another peaceful election, won by Carlos Lleras Restrepo, a Liberal economist. Although lacking the necessary two-thirds majority required under the Colombian constitution to pass legislation, Lleras came to power with the firm support of the press and other important public sectors. His regime occupied itself with increasing public revenues, improving public administration, securing external financial assistance to supplement domestic savings, and preparing new overall and sectoral development plans. In April 1970, Conservative Party leader Misael Pastrana Borrero, a former cabinet minister, was elected president, narrowly defeating former President Rojas. The election results were disputed but later upheld.

In August 1974, with the inauguration of the Liberal Alfonso López Michelsen as president, Colombia returned to a two-party system for presidential and congressional elections. As provided by a constitutional amendment of 1968, President López shared cabinet posts and other positions with the Conservative Party. In 1978, another Liberal candidate, Julio César Turbay Ayala, won the presidency, but because his margin of victory was slim (49.5% against the Conservatives' 46.6%), he continued the tradition of giving a number of cabinet posts to the opposition. In June 1982, just before leaving office, Turbay lifted the state of siege that had been in force intermittently since 1948.

Because of a split in the Liberal Party, the Conservatives won the 1982 elections, and a former senator and ambassador to Spain, Belisario Betancur Cuartas, was sworn in as president in August. He continued the tradition of including opposition party members in his cabinet. But Betancur's most immediate problem was political violence, including numerous kidnappings and political murders since the late 1970s by both left- and right-wing organizations. In 1983, it was estimated that some 6,000 leftist guerrillas were active in Colombia. There were at least four guerrilla groups in the field, of which M-19 was the best known. The Betancur government pursued a policy of negotiation with the guerrillas. He offered amnesty and political recognition in exchange for the cessation of activity and the joining of the electoral process. Betancur's last year in office was marred by a seizure by M-19 of the Palace of Justice. Troops stormed the building, and it was completely destroyed by fire, with over 90 people killed.

The 1986 election went resoundingly to the Liberals under the longtime politician Virgilio Barco Vargas, who campaigned on a platform of extensive economic and social reform, focusing on poverty and unemployment. Barco won a significant majority, but the Conservative Party broke from the traditions started by the National Front, refusing cabinet and other government posts offered. President Barco's rhetoric was not matched by policies of any substance, and the economy continued to stagnate. Barco made no progress with drug traffickers, who arranged for the murder of his attorney-general. However, he was able to initiate a plan aimed at bringing guerrilla groups into the political system.

The election of 1990 brought another Liberal, César Gaviria Trujillo, to the presidency. In that election, three candidates were assassinated. Gaviria continued Barco's outreach to the various leftist guerrilla groups, and in 1991 the notorious M-19 group demobilized and became a political party. The other groups chose to remain active. Gaviria responded to their intransigence in November 1992 by announcing new counterinsurgency measures and a hard-line policy against both guerrillas and drug traffickers. Gaviria also decided to create a new constitution, which occurred on 5 July 1991. It included a number of reforms aimed at increasing the democratization of Colombia's elite-controlled political system.

In the 1994 elections, Colombians continued their preference for Liberal candidates, with Ernesto Samper Pizano winning a runoff election against Conservative TV newscaster Andrés Pastrana. In the general election, only 18,499 votes separated the two candidates. The campaign was again marked by widespread political violence. Samper's government was weakened by charges that he and other senior government officials had accepted money from drug traffickers during the 1994 election campaign. (Congress formally exonerated the president of these charges in 1996.)

The 40-year-old campaign by Marxist guerillas to overthrow the Colombian government continued unabated and even escalated in the 1990s. As of 1996, there was a guerilla presence in over half the country's villages and towns, and it was estimated that about a million Colombians had fled their homes between 1987 and 1997 as a result of rural violence. With forces estimated at 10,000, there was no apparent prospect that guerilla groups would succeed in taking over the country, but they continued to thrive, relying heavily on funds from the drug cartels following the collapse of the Soviet union.

By the 1980s Colombian drug traffickers controlled 80% of the world's cocaine trade. In response to a domestic and international crackdown in the mid- and late 1980s, the powerful Medellín cartel stepped up its terrorist attacks, including car bombings and political assassinations. The leaders of the cartel surrendered to the Gaviria government in 1991, but head boss Pablo Escobar escaped from government custody the following year, and was eventually hunted down and killed in 1993. Most top leaders of the Cali cartel, which had taken over much of the Medellín market, were arrested in 1995 and subsequently imprisoned. However, Colombia's lucrative drug trade continued to flourish.

In 1998, the Conservative Party came back to power when Andrés Pastrana won the presidential election with 50.5% of the vote, defeating Liberal Horacio Serpa. Upon taking office, Pastrana sought more collaboration from the United States to fight the war on drugs and sought to establish peace talks with the guerrillas. But his efforts proved fruitless. The talks with the guerilla leaders he championed led nowhere and his popularity began to fall. The adoption of the Plan Colombia in 2000, a multimillion dollar initiative funded by the US government, aimed at combating drug production generated criticism for its heavy focus on military action rather than economic incentives that could lead peasants to abandon the coca leaf plantation.

In the 2002 presidential election, former Liberal Party leader turned independent Álvaro Uribe easily won with 53.1%, defeating Liberal Party official candidate Horacio Serpa. Conservative Party candidate Luis Garzón withdrew weeks before the election and threw his support behind Uribe. Campaigning on a tough platform against guerrilla leaders and drug traffickers, Uribe promised a relentless fight against organized crime if elected. His inauguration was marked by violent bomb attacks in Colombia's larger cities. The Plan Colombia has been pushed forward but violence has not subdued. During his first year in office, Uribe enjoyed popular support and was been able to build a coalition of Liberal and Conservative legislators to push his tough plan against the guerrillas.

First thing this is a every good website. That give you history of a spanish country in South America that give the United States of America and other country in the world very good coffce bean. Good DAY Night Mornig