Zimbabwe - History

Evidence of Stone Age cultures dating back 100,000 years has been found, and it is thought that the San people, now living mostly in the Kalahari Desert, are the descendants of Zimbabwe's original inhabitants. The remains of ironworking cultures that date back to AD 300 have been discovered. Little is known of the early ironworkers, but it is believed that they were farmers, herdsmen, and hunters who lived in small groups. They put pressure on the San by gradually taking over the land. With the arrival of the Bantu-speaking Shona from the north between the 10th and 11th centuries AD , the San were driven out or killed, and the early ironworkers were incorporated into the invading groups. The Shona gradually developed gold and ivory trade with the coast, and by the mid-15th century had established a strong empire, with its capital at the ancient city of Zimbabwe. This empire, known as Munhumutapa, split by the end of the century, the southern part becoming the Urozwi Empire, which flourished for two centuries.

By the time the British began arriving in the mid-19th century, the Shona people had long been subjected to slave raids. The once-powerful Urozwi Empire had been destroyed in the 1830s by the Ndebele, who, under Mzilikaze, had fled from the Zulus in South Africa. David Livingstone, a Scottish missionary and explorer, was chiefly responsible for opening the whole region to European penetration. His explorations in the 1850s focused public attention on Central Africa, and his reports on the slave trade stimulated missionary activity. In 1858, after visiting Mzilikaze, Robert Moffat, Livingstone's father-in-law, established Inyati Mission, the first permanent European settlement in what is now Zimbabwe.

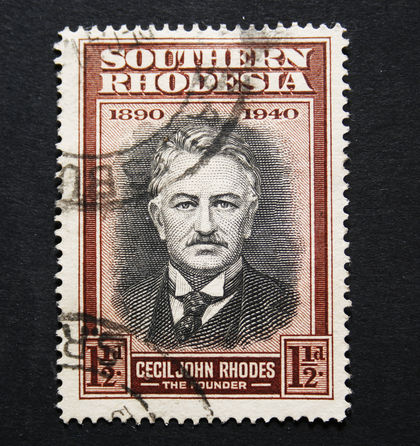

To forestall Portuguese and Boer expansion, both the British government and Cecil Rhodes actively sought to acquire territory. Rhodes, whose fortune had been made through diamond mining in South Africa, became especially active in gaining mineral rights and in sending settlers into Matabeleland (the area occupied by the Ndebele people) and Mashonaland (the area occupied by the Shona people). In 1888, Lobengula, king of the Ndebele, accepted a treaty with Great Britain and granted to Charles Rudd, one of Rhodes's agents, exclusive mineral rights to the lands he controlled. Gold was already known to exist in Mashonaland, so, with the grant of rights, Rhodes was able to obtain a royal charter for his British South Africa Company (BSAC) in 1889. The BSAC sent a group of settlers with a force of European police into Mashonaland, where they founded the town of Salisbury (now Harare). Rhodes gained the right to dispose of land to settlers (a right he was already exercising de facto). With the defeat of the Ndebele and the Shona between 1893 and 1897, Europeans were guaranteed unimpeded settlement. The name Rhodesia was common usage by 1895.

Under BSAC administration, British settlement continued, but conflicts arose between the settlers and the company. In 1923, Southern Rhodesia was annexed to the crown; its African inhabitants thereby became British subjects, and the colony received its basic constitution. Ten years later, the BSAC ceded its mineral rights to the territory's government for £2 million.

After the onset of self-government, the major issue in Southern Rhodesia was the relationship between the European settlers and the African population. The British government, besides controlling the colony's foreign affairs, retained certain powers to safeguard the rights of Africans. In 1930, however, Southern Rhodesia adopted a land apportionment act that was accepted by the British government. Under this measure, about half the total land area, including all the mining and industrial regions and all the areas served by railroads or roads, was reserved for Europeans. Most of the rest was designated as Tribal Trust Land, native purchase land, or unassigned land. Later acts firmly entrenched the policy of dividing land on a racial basis.

In 1953, the Central African Federation was formed, consisting of the three British territories of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), Nyasaland (now Malawi), and Southern Rhodesia, with each territory retaining its original constitutional status. In 1962, in spite of the opposition of the federal prime minister, Sir Roy Welensky, Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia withdrew from the federation with British approval. The federation disbanded in 1963. Southern Rhodesia, although legally still a colony, sought an independent course under the name of Rhodesia.

Political agitation in Rhodesia increased after the UK's granting of independence to Malawi and Zambia. The white-settler government demanded formalization of independence, which it claimed had been in effect since 1923. The African nationalists also demanded independence, but under conditions of universal franchise and African majority rule. The British government refused to yield to settler demands without amendments to the colony's constitution, including a graduated extension of the franchise leading to eventual African rule. Negotiations repeatedly broke down, and on 5 November 1965, Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith declared a state of emergency. On 11 November, the Smith government issued a unilateral declaration of independence (since known as UDI). The British government viewed UDI as illegal and imposed limited economic sanctions, but these measures did not bring about the desired results. In December, the UN Security Council passed a resolution calling for selective mandatory sanctions against Rhodesia. Further attempts at a negotiated settlement ended in failure. In a referendum held on 20 June 1969, the Rhodesian electorate—92% white—approved the establishment of a republic.

The British governor-general, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, resigned on 24 June 1969. The Legislative Council passed the constitution bill in November, and Rhodesia declared itself a republic on 2 March 1970. The UK called the declaration illegal, and 11 countries closed their consulates in Rhodesia. The UN Security Council called on member states not to recognize any acts by the illegal regime and condemned Portugal and South Africa for maintaining relations with Rhodesia.

Problems in Rhodesia deepened after UDI, largely as a result of regional and international political pressure, African nationalist demands, and African guerrilla activities. Members of the African National Council (ANC), an African nationalist group, were increasingly subjected to persecution and arrest. Nevertheless, guerrilla activity continued. The principal African nationalist groups, besides the ANC, were the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU).

A meeting took place in Geneva in October 1976 between the British and Smith governments and four African nationalist groups. Prominent at the meeting were Joshua Nkomo, the leader of ZAPU; Robert Mugabe, leader of ZANU; Bishop Abel Muzorewa of the ANC; and the Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole, former leader of ZANU. Nkomo and Mugabe had previously formed an alliance, the Patriotic Front. The conference was unable to find the basis for a national settlement; but on 3 March 1978, the Smith regime signed an internal agreement with Muzorewa, Sithole, and other leaders, providing for qualified majority rule and universal suffrage. Although Bishop Muzorewa, whose party won a majority in the elections of April 1979, became the first black prime minister of the country (now renamed Zimbabwe-Rhodesia), the Patriotic Front continued fighting.

Meanwhile, the British government had begun new consultations on the conflict, and at the Commonwealth of Nations Conference in Lusaka, Zambia, in August 1979, committed itself to seeking a settlement. Negotiations that began at Lancaster House, in England, on 10 September resulted in an agreement, by 21 December, on a new, democratic constitution, democratic elections, and independence. On 10 December, the Zimbabwe-Rhodesian parliament had dissolved itself, and the country reverted to formal colonial status during the transition period before independence. That month, sanctions were lifted and a cease-fire declared. Following elections held in February, Robert Mugabe became the first prime minister and formed a coalition government that included Joshua Nkomo. The independent nation of Zimbabwe was proclaimed on 18 April 1980, and the new parliament opened on 14 May 1980.

Independence and Factionalism

Following independence, Zimbabwe initially made significant economic and social progress, but internal dissent became increasingly evident. The long-simmering rivalry erupted between Mugabe's dominant ZANU-Patriotic Front Party, which represented the majority Shona ethnic groups, and Nkomo's ZAPU, which had the support of the minority Ndebele. A major point of contention was Mugabe's intention to make Zimbabwe a one-party state. Mugabe ousted Nkomo from the cabinet in February 1982 after the discovery of arms caches that were alleged to be part of a ZAPU-led coup attempt. On 8 March 1983, Nkomo went into exile, but returned to Parliament in August.

Meanwhile, internal security worsened, especially in Matabeleland, where Nkomo supporters resorted to terrorism. The government responded by jailing suspected dissidents, using emergency powers dating from the period of white rule, and by military campaigns against the terrorists. The government's Fifth Brigade, trained by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and loyal to Mugabe, was accused of numerous atrocities against civilians in Matabeleland during 1983. By early 1984, it was reported that many residents in Matabeleland were starving as a result of the military's interruption of food supplies to the area.

Armed dissidents continued to operate in Matabeleland until 1987, and food supplies in the area continued to be inadequate. A round of particularly brutal killings—men, women, and children—occurred late in the year. The violence abated after the two largest political parties, ZANU and ZAPU, agreed to merge in December 1987.

A growing problem, however, was the political instability of Zimbabwe's neighbors to the south and east. In 1986, South African forces raided the premises of the South African black-liberation African National Congress in Harare, and 10,000 Zimbabwean troops were deployed in Mozambique, seeking to keep antigovernment forces in that country from severing Zimbabwe's rail, road, and oil-pipeline links with the port of Beira in Mozambique. Although Beira is the closest port to landlocked Zimbabwe, because of the guerrilla war in Mozambique about 85% of Zimbabwe's foreign trade was passing through South Africa instead.

Despite its reputed commitment to socialism, the Mugabe government was slow to dismantle the socioeconomic structures of the old Rhodesia. Until 1990, the government's hands were tied by the Lancaster House accords. Private property, most particularly large white-owned estates, could not be confiscated without fair market compensation. Nevertheless, economic progress was solid and Zimbabwe seemed to have come to terms with its settler minority. There was only modest resettlement of the landless (52,000 out of 162,000 landless families from 1980 to 1990) and when white farmers were bought out, black politicians often benefited. Some 4,000 white farmers owned more than one-third of the best land.

In March 1992, a controversial Land Acquisition Act was passed calling for the government to purchase half of the mostly white-owned commercial farming land at below-market prices, without the right of appeal, in order to redistribute land to black peasants. However, the government continued to move slowly and not until April 1993 was it announced that 70 farms, totaling 470,000 acres, would be purchased. Unease among whites grew, as did fear of unemployment, already at around 40%. Economic conditions also threatened to derail the Economic Structural Adjustment Program (ESAP) designed by the IMF and the World Bank. ESAP pressed for a market-driven economy, reduction of the civil service, and an end to price controls and commodity subsidies.

Meanwhile, in the March 1990 elections, Mugabe was reelected with 78.3% of the vote. The Zimbabwe Unity Movement (ZUM) candidate, Tekere, received about 21.7% of the vote. For parliament, ZANU-PF got 117 seats; ZUM, two seats; and ZANU-Ndonga, one seat. There was a sharp drop in voter participation, and the election was marred by restrictions on opposition activity and open intimidation of opposition voters. At first, Mugabe insisted that the results were a mandate to establish a one-party state. In 1991, however, growing opposition abroad and domestically, even within ZANU-PF, forced him to postpone his plans. Sensing an erosion of political support, Mugabe restricted human and political rights, weakened the Bill of Rights, placed checks on the judiciary, and tampered with voters' rolls and opposition party financing. The government also suspended the investigation into the 1982–87 Matabeleland Crisis, a decision that prompted a November 1993 reprimand by the OAU's Human Rights Commission.

As the economy sputtered, political opposition grew. In January 1992, Sithole returned from seven years of self-imposed exile in the United States. In July, Ian Smith chaired a meeting of Rhodesian-era parties seeking to form a coalition in opposition to Mugabe. Sithole and his ZANU-Ndonga Party, the United African National Congress, the largely white Conservative Alliance, and Edgar Tekere's ZUM were included. Students, church leaders, trade unionists, and the media began to speak out. In May 1992 a new pressure group, the Forum for Democratic Reform, was launched in preparation for the 1995 elections. Parliamentary and presidential elections in 1995 and 1996 though officially won by ZANU-PF, were discredited by opposition boycotts and low voter turnout. Then in 1997, a homegrown pro-democracy coalition was launched from the constituency for constitutional reform—the National Constitutional Assembly (NCA). The birth of the NCA dovetailed with the growing radicalization of the Zimbabwe Confederation of Trade Unions (ZCTU) and its transformation from a collective bargaining agent for organized urban industrial labor into a broad-based political opposition movement representing a wide spectrum of civil society, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC). The official launch of the MDC at Rufaro Stadium on 11 September 1999 was followed by the first Congress at which Morgan Tsvangirai was elected president, and Gibson Sibanda his deputy. NCA supporters embraced the MDC as a vehicle for implementing the new constitution should the government be amenable to it.

The MDC's first test came in February 2000 at a national referendum for constitutional changes strongly pro-regime. On 12-13 February, voters soundly rejected the proposals much to the chagrin of the ruling party. The results signalled that ZANUPF was not invincible, and they catapulted Morgan Tsvangirai and the MDC into a leading position heading into the 24-25 June parliamentary elections. Again threatened, Mugabe crackdowned on the opposition. In the run-up to and aftermath of the elections, 34 people were killed including Tsvangirai's driver and a poll worker who were killed in a gasoline-bomb attack. Officially, but without the sanction of international observers, ZANU-PF claimed 62 of 120 elective seats in the House of Assembly, with the MDC taking 57 seats with a turnout of 60% of elibible voters.

The credibility the regime was further damaged in the March 9-11 2002 presidential polls, the conduct of which was declared fraudulent by the opposition and—with the exception of the AU and SADC—by the international community. Officially, Mugabe garnered 53.8% of the vote to 40.2% for Tsvangirai while others claimed 6.0%. The government prevented as many voters as possible in urban districts favorable to the MDC from registering, reduced the number of urban polling stations by 50% over the 2000 elections, added 664 rural polling stations, conducted a state media barrage, and intimidated the opposition. By some reports, 31 people were killed in January and February and 366 tortured. The opposition mounted a legal challenge to the results while the Commonwealth suspended Zimbabwe for one year.

By mid-2003, the country faced multiple crises. Owing to negative impacts of land grabbing, squatting, and repossessions of large white farms under the government's fast-track land reform program, some 400,000 jobs had been lost in commercial agriculture. Combined with a 90% loss in productivity in large-scale farming since the 1990s, some 5.5 million people in a population of 11.6 million were in need of food aid. Inflation had reached 228% and a fuel crisis threatened the nation. Strikes and stay-aways crippled production, prompting ever more severe repression by the government. More than 30% of the adult population was infected with the AIDS virus.

Given the devastating social impact of these issues, internal and diplomatic pressures were mounting for Mugabe to abandon his survival strategy in favor of a quick and clean exit strategy. One such move afoot was to offer the MDC a form of transitional government in exchange for cooperation in amending the constitution to allow a managed presidential succession and immunity from prosecution for the president and his followers in their retirement. However, there appeared to be relunctance on the part of Tsvangirai's supporters to offer amnesty to a regime that had committed in excess of 550,000 cases of human rights violations ranging from murder, abduction and rape to arson.

Can somebody help me on this...