Independence of Colonial Peoples - Progress of decolonization

In the 10 years following the adoption of the declaration on the ending of colonialism (1960 to 1970), 27 territories (with a total population of over 53 million) attained independence. Some 44 territories (with a population of approximately 28 million) remained under foreign rule or control, however, and the General Assembly's work in hastening the process of decolonization was far from completed. In Africa, an ever-widening confrontation had emerged between the colonial and white-minority regimes and the roughly 18 million Africans in Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau), Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, and São Tomé and Príncipe; in Southern Rhodesia, which was legally still a British possession; and in the old League of Nations mandate territory of South West Africa, officially designated as Namibia by the UN. Resisting all efforts by the UN to bring an end to white-minority rule by peaceful means, these regimes refused to change despite pressures brought upon them both by the international community and by the demands of the African peoples of the territories.

This refusal had led to the emergence of African national liberation movements within the territories and to a series of armed conflicts that were seen by independent African states as a menace to peace and stability and as the potential cause of a bloody racial war engulfing the whole of Africa. Armed conflict, beginning in 1960 in Angola, had, in fact, spread to all the Portuguese-controlled territories on the African mainland and, as the African liberation movements gained strength and support, had developed into full-scale warfare in Angola, Portuguese Guinea, and Mozambique, engaging large Portuguese armies and putting a serious strain on Portugal's economy.

In Southern Rhodesia and Namibia, armed struggle for liberation was slower to develop, but despite the essential differences in the problems presented by these territories, the General Assembly—partly in response to a growing collaboration between South Africa, Portugal, and the white-minority regime in Southern Rhodesia—had come to view them as aspects of a single consuming issue of white-minority rule versus black-majority rights.

The strategy advocated by the Afro-Asian Group, supported by the Soviet-bloc countries and many others, for rectifying the situation in these territories was essentially to obtain recognition and support for their African national liberation movements and to seek the application, through a Security Council decision made under Chapter VII of the charter, of mandatory enforcement measures, including full economic sanctions and military force as circumstances warranted. However, in each case, except partially in that of Southern Rhodesia, the use of mandatory enforcement measures was decisively resisted by two permanent members of the Security Council, the United Kingdom and the United States, which, together with several other Western nations, felt that they could not afford to embark upon a policy of confrontation with the economically wealthy white-minority regimes of southern Africa.

Despite this resistance, the African and Asian nations continued to maintain the spotlight of attention on issues of decolonization. Year after year, one or another of the cases mentioned above was brought before the Security Council. Each session of the General Assembly, and of the Special Committee on decolonization, was the scene of lengthy and often acrimonious debates. This constant pressure led to greater recognition and status for the national liberation movements of the territories in Africa and brought about widespread condemnation and isolation of the white regimes. In 1971, for the first time, a mission of the Special Committee visited the liberated areas of Guinea-Bissau at the invitation of the African liberation movement concerned and found that the liberation movement had established an effective administration.

In 1972, the General Assembly affirmed for the first time that "the national liberation movements of Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, and Mozambique are the authentic representatives of the true aspirations of the peoples of those territories" and recommended that, pending the independence of those territories, all governments and UN bodies should, when dealing with matters pertaining to the territories, ensure the representation of those territories by the liberation movements concerned. In the following year, the General Assembly extended similar recognition to the national liberation movements of Southern Rhodesia and Namibia.

On 25 April 1974, largely as a result of internal and external pressures resulting from its colonial wars, a change of regime occurred in Portugal that had major repercussions on the situation in its African territories. The new regime pledged itself to ending the colonial wars and began negotiations with the national liberation movements. By the end of 1974, Portuguese troops had been withdrawn from Guinea-Bissau and the latter had become a UN member. This was followed by the independence and admission to UN membership of Cape Verde, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe in 1975 and Angola in 1976.

Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

The problem of Southern Rhodesia, which in 1977 had a population of almost 7 million, of whom 6.5 million were Africans, was not resolved until the end of the decade.

Southern Rhodesia had been given full internal self-government by the United Kingdom in 1923, although under a constitution that vested political power exclusively in the hands of the white settlers. Hence, the United Kingdom did not include this dependency in its original 1946 list of non-self-governing territories and did not transmit information on it to the UN. Although, by the terms of the 1923 constitution, the United Kingdom retained the residual power to veto any legislation contrary to African interests, this power was never used, and no attempt was made to interfere with the white settlers' domination of the territorial government.

UN involvement in the question of Southern Rhodesia began in 1961, when African and Asian members tried, without success, to bring pressure to bear upon the United Kingdom not to permit a new territorial constitution to come into effect. While giving Africans their first representation in the Southern Rhodesian parliament, the 1961 constitution restricted their franchise through a two-tier electoral system heavily weighted in favor of the European community.

In June 1962, acting on the recommendation of the Special Committee, the General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring Southern Rhodesia to be a non-self-governing territory within the meaning of Chapter XI of the charter, on the grounds that the vast majority of the people of Southern Rhodesia were denied equal political rights and liberties. The General Assembly requested the United Kingdom to convene a conference of all political parties in Rhodesia for the purpose of drawing up a new constitution that would ensure the rights of the majority on the basis of "one-man, one-vote." However, the United Kingdom continued to maintain that it could not interfere in Rhodesia's domestic affairs. The 1961 constitution duly came into effect in November 1962.

On 11 November 1965, the government of Ian Smith unilaterally declared Southern Rhodesia independent. The United Kingdom, after branding the declaration an "illegal act," brought the matter to the Security Council on the following day, and a resolution was adopted condemning the declaration and calling upon all states to refrain from recognizing and giving assistance to the "rebel" regime. On 20 November, the council adopted a resolution condemning the "usurpation of power," calling upon the United Kingdom to bring the regime to an immediate end, and requesting all states, among other things, to sever economic relations and institute an embargo on oil and petroleum products. In 1968, the Security Council imposed wider mandatory sanctions against Southern Rhodesia and established a committee to oversee the application of the sanctions. The General Assembly urged countries to render moral and material assistance to the national liberation movements of Zimbabwe, the African name for the territory.

On 2 March 1970, Southern Rhodesia proclaimed itself a republic, thus severing its ties with the United Kingdom. After Mozambique became independent in 1975, guerrilla activity along the border with Southern Rhodesia intensified; the border was then closed, further threatening the economy of Southern Rhodesia, already hurt by UN-imposed sanctions.

In 1977, Anglo-American proposals for the settlement of the Southern Rhodesian problem were communicated to the Security Council by the United Kingdom. The proposals called for the surrender of power by the illegal regime, free elections on the basis of universal suffrage, the establishment by the United Kingdom of a transitional administration, the presence of a UN force during the transitional period, and the drafting of an independence constitution. The proposals were to be discussed at a conference of all political parties in Southern Rhodesia, white and African. However, the regime rejected the idea of such a conference. Attempts by the regime in 1978 and early 1979 to draft a new constitution giving some political power to Africans but maintaining effective control by the white minority failed, and the struggle by forces of the liberation movement, called the Patriotic Front, intensified.

In August 1979, British prime minister Margaret Thatcher stated at the Conference of Commonwealth Heads of State and Government that her government intended to bring Southern Rhodesia to legal independence on a basis acceptable to the international community. To this end, a constitutional conference was convened in London on 10 September, to which representatives of the Patriotic Front and the Rhodesian administration in Salisbury were invited. On 21 December, an agreement was signed on a draft independence constitution and on transitional arrangements for its implementation, as well as on a cease-fire to take effect on 28 December. Lord Soames was appointed governor of the territory until elections, which took place in February 1980 in the presence of UN observers. On 11 March, Lord Soames formally appointed Robert G. Mugabe, whose party had received the majority of seats in the House of Assembly, as prime minister. The independence of Zimbabwe was proclaimed on 18 April 1980, and on 25 August, Zimbabwe became a member of the UN.

Remaining Colonial Issues

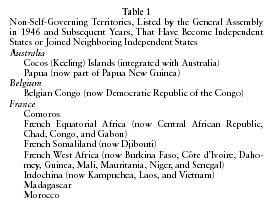

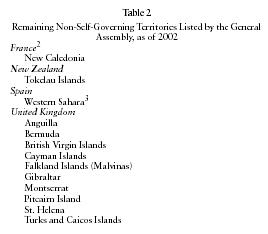

The 16 remaining dependent territories are almost all small islands scattered about the globe. Their tiny populations and minimal economic resources render it almost impossible for them to survive as viable, fully independent states. Table 1 sets forth all the former non-self-governing territories that have become independent or joined neighboring independent states. Table 2 lists the remaining non-self-governing territories.

Although the administering powers joined with the rest of the UN membership in asserting that the peoples of these small territories have an inalienable right to the exercise of self-determination, the leaders of the drive to end colonialism have doubted the genuineness of the preparations for achieving this goal. As evidence to justify their skepticism, the African and Asian nations pointed out that military bases were established in some of the small territories, which they declared "incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter." Moreover, in the case of territories that the administering powers have declared their intention of preparing for self-governing status rather than for full independence, the majority of UN members feel that the General Assembly should be granted an active role in ascertaining the wishes of the inhabitants and furnished with more comprehensive information on conditions prevailing in the territories. The General Assembly has approved numerous resolutions requesting the administering states to allow UN missions to visit the remaining non-self-governing territories to ascertain, firsthand, the wishes of the inhabitants, but has met with little cooperation.

Two of the territories that have been brought under the General Assembly's surveillance through the Special Committee are United Kingdom possessions in which the issue of decolonization is complicated by conflicting claims of sovereignty by other nations—the Falkland Islands (Malvinas), also claimed by Argentina, and Gibraltar, also claimed by Spain.

With regard to another territory, Western Sahara, Spain informed the Secretary-General in 1976 that it had terminated its presence in the territory and considered itself henceforth exempt from any international responsibility in connection with its administration. Western Sahara, however, continued to be listed by the General Assembly as non-self-governing.

The Special Committee annually reviews the list of territories to which the declaration on decolonization is applicable. In 1986, France, the administering power of New Caledonia, refused to recognize the competence of the committee over the territory or to transmit to the UN the information called for under Article 73(e) of the charter. France has, however, asserted that it will respect the wishes of the majority of the people of New Caledonia, in accordance with the provisions of the Matignon Agreement agreed to by all the parties in 1988. As a result of the Nouméa Accord of 1998, the New Caledonian parties opted for a negotiated solution and progressive autonomy from France rather than an immediate referendum. The transfer of powers from France began in 2000 and will continue for 15 to 20 years, when the territory will opt for full independence or a form of associated statehood. As of 2002, New Caledonia continued to vote in French presidential elections and to elect parliamentary representatives to the French Senate and National Assembly. However, new political institutions were formed in New Caledonia as a result of the Nouméa Accord, and they continued to function throughout 2001 and 2002.

The Problem of Namibia (South West Africa)

The status of South West Africa (officially designated as Namibia by the General Assembly in June 1968), a pre-World War I German colony that was administered by South Africa under a League of Nations mandate beginning in 1920, has preoccupied the General Assembly almost from the first moment of the UN's existence. In 1946, South Africa proposed that the Assembly approve its annexation of the territory. Fearing that the South African government would seek to extend its apartheid system to South West Africa, the General Assembly did not approve the proposal and recommended instead that the territory be placed under the UN trusteeship system. In the following year, South Africa informed the General Assembly that while it agreed not to annex the territory, it would not place it under trusteeship. Although South Africa had reported on conditions in the territory in 1946, it declined to submit further reports, despite repeated requests from the General Assembly.

In 1950, the International Court of Justice, in an advisory opinion requested by the General Assembly, held that South Africa continued to have international obligations to promote to the utmost the material and moral well-being and social progress of the inhabitants of the territory as a sacred trust of civilization, and that the UN should exercise the supervisory functions of the League of Nations in the administration of the territory. South Africa refused to accept the court's opinion and continued to oppose any form of UN supervision over the territory's affairs.

In October 1966, the General Assembly, declaring that South Africa had failed to fulfill its obligations under the League of Nations mandate to ensure the well-being of the people of the territory and that it had, in fact, disavowed the mandate, decided that the mandate was therefore terminated, that South Africa had no other right to administer the territory, and that thenceforth the territory came under the direct responsibility of the UN. In May 1967, the General Assembly established the UN Council for South West Africa (later renamed the UN Council for Namibia) to administer the territory until independence "with the maximum possible participation of the people of the territory." It also decided to establish the post of UN Commissioner for Namibia to assist the council in carrying out its mandate. Later in the same year, in the face of South Africa's refusal to accept its decision and to cooperate with the UN Council for Namibia, the General Assembly recommended that the Security Council take measures to enable the UN Council for Namibia to carry out its mandate.

In its first resolution on the question, in 1969, the Security Council recognized the termination of the mandate by the General Assembly, described the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia as illegal, and called on South Africa to withdraw its administration from the territory immediately. In the following year, the Security Council explicitly declared for the first time that "all acts taken by the government of South Africa on behalf of or concerning Namibia after the termination of the mandate are illegal and invalid." This view was upheld in 1971 by the International Court of Justice, which stated, in an advisory opinion requested by the Security Council, that "the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia being illegal, South Africa is under obligation to withdraw its administration from Namibia immediately and thus put an end to its occupation of the territory." South Africa, however, again refused to comply with UN resolutions on the question of Namibia, and it continued to administer the territory.

To secure for the Namibians "adequate protection of the natural wealth and resources of the territory which is rightfully theirs," the UN Council for Namibia enacted a Decree for the Protection of the Natural Resources of Namibia in September 1974. Under the decree, no person or entity may search for, take, or distribute any natural resource found in Namibia without the council's permission, and any person or entity contravening the decree "may be held liable in damages by the future government of an independent Namibia." The council also established, in the same year, the Institute for Namibia (located in Lusaka, Zambia, until South Africa's withdrawal from Namibia) to provide Namibians with education and training and equip them to administer a future independent Namibia.

In 1976, the Security Council demanded for the first time that South Africa accept elections for the territory as a whole under UN supervision and control so that the people of Namibia might freely determine their own future. It condemned South Africa's "illegal and arbitrary application … of racially discriminatory and repressive laws and practices in Namibia," its military buildup, and its use of the territory "as a base for attacks on neighboring countries."

In the same year, the General Assembly condemned South Africa "for organizing the so-called constitutional talks at Wind-hoek, which seek to perpetuate the apartheid and homelands policies as well as the colonial oppression and exploitation of the people and resources of Namibia." It decided that any independence talks regarding Namibia must be between the representatives of South Africa and the South West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO), which it recognized as "the sole and authentic representative of the Namibian people." In 1977, the General Assembly declared that South Africa's decision to annex Walvis Bay, Namibia's main port, was "illegal, null, and void" and "an act of colonial expansion," and it condemned the annexation as an attempt "to undermine the territorial integrity and unity of Namibia."

At a special session on Namibia in May 1978, the General Assembly adopted a declaration on Namibia and a program of action in support of self-determination and national independence for Namibia. Expressing "full support for the armed liberation struggle of the Namibian people under the leadership of the SWAPO," it stated that any negotiated settlement must be arrived at with the agreement of SWAPO and within the framework of UN resolutions.

The UN Plan for Namibian Independence. In July 1978, the Security Council met to consider a proposal by the five Western members of the council—Canada, France, the Federal Republic of Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States—for a settlement of the Namibian question. The proposal comprised a plan for free elections to a constituent assembly under the supervision and control of a UN representative, assisted by a UN transition assistance group that would include both civilian and military components. The council took note of the Western proposal and requested the Secretary-General to appoint a special representative for Namibia. In September 1978, after approving a report by the Secretary-General based on his special representative's findings, the council, in Resolution 435 (1978), endorsed the UN plan for the independence of Namibia, and it decided to establish, under its authority, the UN Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) to ensure the early independence of Namibia through free and fair elections under UN supervision and control.

The Secretary-General's report stated that the implementation of the UN plan would be carried out in three stages: (1) cessation of all hostile acts by all parties; (2) the repeal of discriminatory or restrictive laws, the release of political prisoners, and the voluntary return of exiles and refugees; and (3) the holding of elections after a seven-month pre-electoral period, to be followed by the entry into force of the newly adopted constitution and the consequent achievement of independence by Namibia.

Since 1978, the General Assembly has continually reaffirmed that Security Council Resolution 435 (1978), in which the council endorsed the UN plan for the independence of Namibia, is the only basis for a peaceful settlement. It has condemned South Africa for obstructing the implementation of that resolution and other UN resolutions, for "its manoeuvres aimed at perpetuating its illegal occupation of Namibia," and for its attempts to establish a "linkage" between the independence of Namibia and "irrelevant, extraneous" issues, such as the presence of Cuban troops in Angola. In furtherance of the objective of bringing to an end South Africa's occupation of Namibia, the General Assembly has called upon all states to sever all relations with South Africa, and it has urged the Security Council to impose mandatory comprehensive sanctions against South Africa. The General Assembly also has continued to authorize the UN Council for Namibia, as the legal administering authority for Namibia, to mobilize international support for the withdrawal of the illegal South African administration from Namibia, to counter South Africa's policies against the Namibian people and against the UN, to denounce and seek the rejection by all states of South Africa's attempts to perpetuate its presence in Namibia, and to ensure the nonrecognition of any administration or political entity installed in Namibia, such as the so-called interim government imposed in Namibia on 17 June 1985, that is not the result of free elections held under UN supervision and control.

In April 1987, the Secretary-General reported to the Security Council that agreement had been reached on the system of proportional representation for the elections to be held in Namibia as envisaged in Council Resolution 435 (1978). Thus, he noted, all outstanding issues had been resolved, and the only reason for the delay in the emplacement of UNTAG and an agreement on a cease-fire was South Africa's unacceptable precondition that the Cuban troops be withdrawn from Angola before the implementation of the UN plan for Namibian independence.

In December 1988, after eight months of intense negotiations brokered by the United States, Angola, Cuba, and South Africa signed agreements on the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola and the achievement of peace in south-western Africa. On 16 January 1989 the Security Council officially declared that Namibia's transition to independence would begin on 1 April 1989 (Security Council Resolution 628/1989). The council also authorized sending the UNTAG to Namibia to supervise the transition (Security Council Resolution 629/1989).

In one short year, from 1 April 1989 to 21 March 1990, the 8,000-member UNTAG force established 200 outposts, including 42 regional or district centers and 48 police stations. During the transition the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had supervised the repatriation of 433,000 Namibian exiles who had been scattered throughout 40 countries. UNTAG supervised the registration of more than 700,000 voters, more than 97% of whom cast ballots in the historic election from 7–11 November 1989 that marked the end of Namibia's colonial history. The Special Committee also dispatched a visiting mission to observe and monitor the election process. In that election Sam Nujoma, head of SWAPO, was elected the country's first president. The mission reported to the Special Committee that the people of Namibia had, in accordance with Security Council resolution 435 (1978), exercised their inalienable right to self-determination by choosing their representatives to a constituent assembly that was charged with drafting a constitution for an independent Namibia.

In March 1990, Secretary-General Perez de Cuéllar administered the oath of office to the new Namibian president at a historic celebration. In a moving show of good faith, President F. W. DeKlerk of South Africa took part in the inauguration ceremony. Nelson Mandela, then leader of South Africa's African National Congress party and only recently released from prison in South Africa, also attended, as did hundreds of dignitaries from 70 countries.

On 23 April 1990 Namibia became the 159th member of the United Nations.

| Table 1 |

| Non-Self-Governing Territories, Listed by the General Assembly in 1946 and Subsequent Years, That Have Become Independent States or Joined Neighboring Independent States Australia |

| Cocos (Keeling) Islands (integrated with Australia) |

| Papua (now part of Papua New Guinea) |

| Belgium |

| Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) France |

| Comoros |

| French Equatorial Africa (now Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, and Gabon) French Somaliland (now Djibouti) |

| French West Africa (now Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Dahomey, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal) |

| Indochina (now Kampuchea, Laos, and Vietnam) |

| Madagascar |

| Morocco |

| New Hebrides (Anglo-French condominium; now Vanuatu) |

| Tunisia |

| Netherlands |

| Netherlands Indies (now Indonesia) |

| Suriname |

| West New Guinea (West Irian; now part of Indonesia) |

| New Zealand |

| Cook Islands (self-governing in free association with New Zealand) |

| Niue (self-governing in free association with New Zealand) |

| Portugal |

| Angola |

| Cape Verde |

| Goa (united with India) |

| Mozambique |

| Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau) |

| São Tomé and Príncipe |

| Spain |

| Fernando Poo and Rio Muni (now Equatorial Guinea) |

| Ifni (returned to Morocco) |

| United Kingdom |

| Aden (now part of Yemen) |

| Antigua (now Antigua and Barbuda) |

| Bahamas |

| Barbados |

| Basutoland (now Lesotho) |

| Bechuanaland (now Botswana) |

| British Guiana (now Guyana) |

| British Honduras (now Belize) |

| British Somaliland (now Somalia) |

| Brunei (now Brunei Darussalam) |

| Cyprus |

| Dominica |

| Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu) |

| Fiji |

| Gambia |

| Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati) |

| Gold Coast (now Ghana) |

| Grenada |

| Jamaica |

| Kenya |

| Malaya (now Malaysia) |

| Malta |

| Mauritius |

| Nigeria |

| New Hebrides (Anglo-French condominium; now Vanuatu) |

| North Borneo (now part of Malaysia) |

| Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) |

| Nyasaland (now Malawi) |

| Oman |

| St. Kitts and Nevis |

| St. Lucia |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines |

| Sarawak (now part of Malaysia) |

| Seychelles |

| Sierra Leone |

| Singapore |

| Solomon Islands |

| Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) |

| Swaziland |

| Trinidad and Tobago |

| Uganda |

| Zanzibar (now part of Tanzania) |

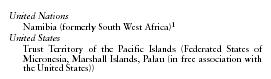

| United Nations |

| Namibia (formerly South West Africa) 1 |

| United States |

| Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Palau (in free association with the United States)) |

1. In 1966, the General Assembly terminated South Africa's mandate over South West Africa and placed the territory under the direct responsibility of the UN. In 1968, the General Assembly declared that the territory would be called Namibia, in accordance with its people's wishes. Until independence, the legal administering authority for Namibia was the UN Council for Namibia.

| Table 2 |

| Remaining Non-Self-Governing Territories Listed by the General Assembly, as of 2002 |

| France 2 |

| New Caledonia |

| New Zealand |

| Tokelau Islands |

| Spain |

| Western Sahara 3 |

| United Kingdom |

| Anguilla |

| Bermuda |

| British Virgin Islands |

| Cayman Islands |

| Falkland Islands (Malvinas) |

| Gibraltar |

| Montserrat |

| Pitcairn Island |

| St. Helena |

| Turks and Caicos Islands |

| United States |

| American Samoa |

| Guam United States Virgin Islands |

2. On 2 December 1986, the General Assembly decided that New Caledonia was a non-self-governing territory within the meaning of Chapter XI of the UN Charter.

3. Spain informed the Secretary-General on 26 February 1976 that as of that date, it had terminated its presence in the territory of the Sahara and deemed it necessary to place the following on record: "Spain considers itself henceforth exempt from any responsibility of an international nature in connection with the administration of the territory in view of the cessation of its participation in the temporary administration established for the territory." On 5 December 1984, and in many subsequent resolutions, the General Assembly reaffirmed that the question of Western Sahara was a question of decolonization, which remained to be resolved by the people of Western Sahara. In August 1988 the Kingdom of Morocco and the Frente Popular para la Liberación (Polisario Front) agreed in principle to the proposals put forward by Secretary-General Perez de Cuéllar and the Organization of African Unity. By its Resolutions 658 (1990) and 690 (1991) the Security Council adopted a settlement plan for Western Sahara that included a referendum for self-determination by the people of the country. In September 1991, the UN achieved a cease-fire in Western Sahara between the factions, through the establishment of the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). In 1994, MINURSO began the process of identifying potential voters. In May 1996, the Secretary-General suspended the identification process and most MINURSO civilian staff were withdrawn. The military component remained to monitor and verify the ceasefire. In October 1998, in an attempt to move the process of a referendum forward, the Secretary-General presented a package of measures to the parties, which included a protocol on identification of those remaining applicants from the three tribal groupings. Frente POLISARIO accepted the package the following month, and the government of Morocco accepted in principle in March 1999. As of 2002, the identification process had been completed, but the parties continued to hold divergent views regarding an appeals process, the repatriation of refugees and other aspects of the plan.