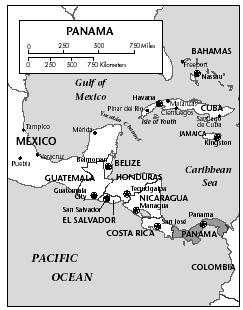

Panama - Political background

Rodrigo de Bastidas was the first Spanish conqueror to visit the Isthmus of Panama in 1502. A year later, Christopher Columbus established a temporary settlement in the region, and in 1513, Vasco Nunez de Balboa walked from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean, proving that the Isthmus was the shortest passage to link the two oceans. Since then Panama became a center of trade for the colonial power. Gold and other goods were shipped from South America and were hauled across the Isthmus to be loaded to other ships waiting on the Caribbean Sea. Due to its strategic importance and its convenient location for trade between Europe and South America, Panama became a key colony of the Spanish Empire from 1538 to 1821. After some unsuccessful attempts at independence, Panama was incorporated as a province of the newly formed Republic of Colombia and it remained as such until 1903. In the late 19th century, French entrepreneurs eyed the Isthmus of Panama to build a new transoceanic canal. Ferdinand de Lesseps led the effort from 1890 to 1900, but the dense jungle, tropical diseases, and shortage of labor derailed his attempt.

In 1903, with encouragement from the United States and financial support from the French, Panama declared its independence from Colombia. A treaty with the United States set the legal and political basis for U.S. involvement in building the canal. The Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty granted land rights to the United States in perpetuity in a 16-km (10 mi) wide corridor between the two oceans. In total, Panama ceded a 1380-sq km (533-sq km) strip of land that divided the west and east regions of the country. The United States completed the 80-km (50-mi) long canal in 1914. From 1903 until the 1950s, a commercial elite controlled political power although Panama was nominally a constitutional democracy. The military began mounting pressure upon the government and demanded a greater role in the administration and in the profit sharing from the revenues of the canal. In addition, the large U.S. military presence in the country caused discontent among the military elite.

In October of 1968, President Arnulfo Arias, who had been elected president twice before and had been ousted as many times, was removed from office a third time by the Panamanian military. Brigadier General Omar Torrijos, the head of the National Guard, emerged as the leader of the military junta and eventually seized total control. A charismatic leader, Torrijos continued the practices of corruption and repression that had characterized his predecessors. His leading cause, however, was to repeal the 1903 Canal Treaty and recover control of the land where the canal had been built. Popular riots in 1964 led to the death of four U.S. marines and more than 20 Panamanians. U.S. and Panamanian negotiators proposed a new treaty in 1967 but neither country ratified the agreement. In 1973, new negotiations were initiated after the two countries signed a protocol known as the Kissinger-Tack declaration of principles. On 7 September 1977, President Jimmy Carter and General Torrijos signed the Panama Canal Treaty in Washington, D.C. After being approved by the Panamanians in a national plebiscite in October of the same year, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty in 1978. The new treaty granted the United States primary responsibility for the operation and defense of the canal until December of 1999. At that time, responsibility for the operation of the canal would be transferred to Panama, but U.S. military vessels would still have priority of passage. Panama would allow equal access to the canal, and the United States would have the right to ensure that the canal remains open at all times. Together with the canal treaty negotiations, Torrijos initiated a process of transition to democracy. He formed the Democratic Revolutionary Party and amended the 1972 Constitution to allow for the reorganization of the unicameral legislative body. When Torrijos died in a plane accident in 1981, a political vacuum ensued.

Eventually, General Manuel Antonio Noriega emerged as the strongman of Panamanian politics. Although there were six different presidents during the 1980s, actual power remained in the hands of Noriega. In 1989, when opposition candidates won victories in the elections, Noriega suspended the presidential elections. Political and social turmoil, aggravated by an ongoing economic crisis, threatened stability in Panama. Amid accusations of that the government was corrupt and linked to drug cartels, the United States invaded Panama on 20 December 1989. Noriega was captured and taken to the United States to face charges; he received a 40-year jail sentence for drug trafficking.

Guillermo Endara, a man of no political experience, was installed as president and governed until 1994. Inefficiency and corruption characterized his government, and the economic situation worsened. Ernesto Pérez Balladares of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) won the 1994 elections and assumed power. He restored political and social order and began a process of neoliberal economic reforms aimed at restoring growth, reducing inflation, and creating employment. By the end of his administration, however, the economy was still in crisis. Pérez Balladares attempted to modify the Constitution to run for a second term in 1999, but he failed to muster a sufficient majority in the unicameral legislature. Elections held in May 1999 resulted in a victory for Mireya Moscoso, who became the first female president of Panama.

Panama is a representative democracy with three branches of government: executive and legislative branches elected by direct, secret vote for 5-year terms, and an independent appointed judiciary. The executive branch includes a president and two vice presidents. The legislative branch consists of a 72-member unicameral Legislative Assembly. The judicial branch is organized under a nine-member Supreme Court and includes all tribunals and municipal courts. An autonomous Electoral Tribunal supervises voter registration, the election process, and the activities of political parties. Everyone over the age of 18 is required to vote, although those who fail to do so are not penalized.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: