Slovenia - History

Origins and Middle Ages

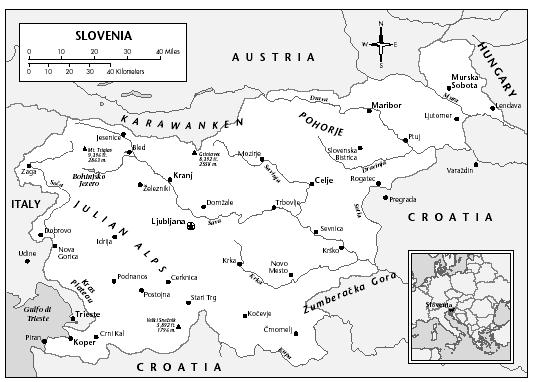

Slovenia is located in the central European area where Latin Germanic, Slavic, and Magyar people have come into contact with one another. The historical dynamics of these four groups have impacted the development of this small nation.

Until the 8th–9th centuries AD , Slavs used the same common Slavic language that was codified by St. Cyril and Methodius in their AD 863 translations of Holy Scriptures into the Slavic tongue. Essentially an agricultural people, the Slovenes settled from around AD 550 in the eastern Alps and in the western Pannonian Plains. The ancestors of today's Slovenes developed their own form of political organization in which power was delegated to their rulers through an "electors" group of peasant leaders/soldiers (the "Kosezi"). Allies of the Bavarians against the Avars, whom they defeated in AD 743, the Carantania Slovenes came under control of the numerically stronger Bavarians and both were overtaken by the Franks in AD 745.

In 863, the Greek scholars Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius were sent to Moravia, having first developed an original alphabet (called "Glagolitic") and translated the necessary Holy Scriptures into the Slavic tongue of the time. The work of the two "Apostles of the Slavs" was opposed by the Frankish Bishops who accused them of teaching heresy and using a non-sacred language and script. Invited by Pope Nicholas I to Rome to explain their work, the brothers visited with the Slovene Prince Kocelj in 867 and took along some 50 young men to be instructed in the Slavic scriptures and liturgy that were competing with the traditionally "sacred" liturgical languages of Latin and Greek. Political events prevented the utilization of the Slavic language in Central European Churches with the exception of Croatia and Bosnia. However, the liturgy in Slavic spread among Balkan and Eastern Slavs.

Slovenes view the installation of the Dukes of Carinthia with great pride as the expression of a non-feudal, bottom-up delegation of authority—by the people's "electors" through a ceremony inspired by old Slavic egalitarian customs. All the people assembled would intone a Slovene hymn of praise—"Glory and praise to God Almighty, who created heaven and earth, for giving us and our land the Duke and master according to our will."

This ceremony lasted for 700 years with some feudal accretions and was conducted in the Slovenian language until the last one in 1414. The uniqueness of the Carinthian installation ceremony is confirmed by several sources, including medieval reports, the writing of Pope Pius II in 1509, and its recounting in Jean Bodin's Treatise on Republican Government (1576) as "unrivaled in the entire world." In fact, Thomas Jefferson's copy of Bodin's Republic contains Jefferson's own initials calling attention to the description of the Carinthian installation and therefore, to its conceptual impact on the writer of the American Declaration of Independence.

The eastward expansion of the Franks in the 9th century brought all Slovene lands under Frankish control. Carantania then lost its autonomy and, following the 955 victory of the Franks over the Hungarians, the Slovene lands were organized into separate frontier regions. This facilitated their colonization by German elements while inhibiting any effort at unifying the shrinking Slovene territories. Under the feudal system, various families of mostly Germanic nobility were granted fiefdoms over Slovene lands and competed among themselves bent on increasing their holdings.

The Bohemian King Premysl Otokar II was an exception and attempted to unite the Czech, Slovak, and Slovene lands in the second half of the 13th century. Otokar II acquired the Duchy of Austria in 1251, Styria in 1260, and Carinthia, Carniola, and Istria in 1269, thus laying the foundation for the future Austrian empire. However, Otokar II was defeated in 1278 by a Hapsburg-led coalition that conquered Styria and Austria by 1282. The Hapsburgs, of Swiss origin, grew steadily in power and by the 15th century became the leading Austrian feudal family in control of most Slovene lands.

Christianization and the feudal system supported the Germanization process and created a society divided into "haves" (German) and "have nots" (Slovene), which were further separated into the nobility/urban dwellers versus the Slovene peasants/serfs. The Slovenes were deprived of their original, egalitarian "Freemen" rights and subjected to harsh oppression

of economic, social, and political nature. The increasing demands imposed on the serfs due to the feudal lords' commitment in support of the fighting against the Turks and the suffering caused by Turkish invasions led to a series of insurrections by Slovene and Croat peasants in the 15th to 18th centuries, cruelly repressed by the feudal system.

Reformation

The Reformation gave an impetus to the national identity process through the efforts of Protestant Slovenes to provide printed materials in the Slovenian language in support of the Reformation movement itself. Martin Luther's translation of the New Testament into German in 1521 encouraged translations into other vernaculars, including the Slovenian. Thus Primoz Trubar, a Slovenian Protestant preacher and scholar, published the first Catechism in Slovenian in 1551 and, among other works, a smaller elementary grammar (A becedarium ) of the Slovenian language in 1552. These works were followed by the complete Slovenian translation of the Bible by Jurij Dalmatin in 1578, printed in 1584. The same year Adam Bohoric published, in Latin, the first comprehensive grammar of the Slovenian language which was also the first published grammar of any Slavic language. The first Slovenian publishing house (1575) and a Jesuit College (1595) were established in Ljubljana, the central Slovenian city and between 1550 and 1600 over 50 books in Slovenian were published. In addition, Primoz Trubar and his coworkers encouraged the opening of Slovenian elementary and high schools. This sudden explosion of literary activity built the foundation for the further development of literature in Slovenian and its use by the educated classes of Slovenes. The Catholic Counter-Reformation reacted to the spread of Protestantism very strongly within Catholic Austria, and slowed down the entire process until the Napoleonic period. Despite these efforts, important cultural institutions were established, such as an Academy of Arts and Sciences (1673) and the Philharmonic Society in 1701 (perhaps the oldest in Europe).

The Jesuits, heavily involved in the Counter-Reformation, had to use religious literature and songs in the Slovene language, but generally Latin was used as the main language in Jesuit schools. However, the first Catholic books in Slovenian were issued in 1615 to assist priests in the reading of Gospel passages and delivery of sermons. The Protestant books in Slovenian were used for such purposes, and they thus assisted in the further development of a standard literary Slovenian. Since Primoz Trubar used his dialect from the Carniola region, it heavily influenced the literary standard. From the late 17th and through the 18th century the Slovenes continued their divided existence under Austrian control.

Standing over trade routes connecting the German/Austrian hinterland to the Adriatic Sea and the Italian plains eastward into the Balkan region, the Slovenes partook of the benefits from such trade in terms of both economic and cultural enrichment. Thus by the end of the 18th century, a significant change occurred in the urban centers where an educated Slovene middle class came into existence. Deeply rooted in the Slovene peasantry, this element ceased to assimilate into the Germanized mainstream and began to assert its own cultural/national identity. Many of their sons were educated in German, French, and Italian universities and thus exposed to the influence of the Enlightenment. Such a person was, for instance, Baron Ziga Zois (1749–1819), an industrialist, landowner, and linguist who became the patron of the Slovene literary movement. When the ideas of the French Revolution spread through Europe and the Napoleonic conquest reached the Slovenes, they were ready to embrace them.

During the reign of Maria Teresa (1740–80) and Joseph II (1780–90), the influence of Jansenism—the emancipation of serfs, the introduction of public schools (in German), equality of religions, closing of monasteries not involved in education or tending to the sick—weakened the hold of the nobility. On the other hand, the stronger Germanization emphasis generated resistance to it from an awakening Slovene national consciousness and the publication of Slovene nonreligious works, such as Marko Pohlin's Abecedika (1765), a Carniolan Grammar (1783) with explanations in German, and other educational works in Slovenian, which include a Slovenian-German-Latin dictionary (1781). Pohlin's theory of metrics and poetics became the foundation of secular poetry in Slovenian, which reached its zenith only 50 years later with France Prešeren (1800–49), still considered the greatest Slovene poet. Just prior to the short Napoleonic occupation of Slovenia, the first Slovenian newspaper was published in 1797 by Valentin Vodnik (1758–1819), a very popular poet and grammarian. The first drama in Slovenian appeared in 1789 by Anton Tomaz Linhart (1756–95), playwright and historian of Slovenes and South Slavs. Both authors were members of Baron Zois' circle.

Napoleon and the Spring of Nations

When Napoleon defeated Austria and established his Illyrian Provinces (1809–13), comprising the southern half of the Slovenian lands, parts of Croatia, and Dalmatia all the way to Dubrovnik with Ljubljana as the capital, the Slovene language was encouraged in the schools and also used, along with French, as an official language in order to communicate with the Slovene population. The four-year French occupation served to reinforce the national awakening of the Slovenes and other nations that had been submerged through the long feudal era of the Austrian Empire. Austria, however, regained the Illyrian Provinces in 1813 and reestablished its direct control over the Slovene lands.

The 1848 "spring of nations" brought about various demands for national freedom of Slovenes and other Slavic nations of Austria. An important role was played by Jernej Kopitar with his influence as librarian/censor in the Imperial Library in Vienna, as the developer of Slavic studies in Austria, as the mentor to Vuk Karadzić (one of the founders of the contemporary Serbo-Croatian language standard), as the advocate of Austro-Slavism (a state for all Slavs of Austria), and as author of the first modern Slovenian grammar in 1808. In mid-May 1848, the "United Slovenia" manifesto demanded that the Austrian Emperor establish a Kingdom of Slovenia with its own parliament, consisting of the then separate historical regions of Carniola, Carinthia, Styria, and the Littoral, with Slovenian as its official language. This kingdom would remain a part of Austria, but not of the German Empire. While other nations based their demands on the "historical statehood" principle, the Slovenian demands were based on the principle of national self-determination some 70 years before American President Woodrow Wilson would embrace the principle in his "Fourteen Points."

Matija Kavcic, one of 14 Slovenian deputies elected to the 1848–49 Austrian parliament, proposed a plan of turning the Austrian Empire into a federation of 14 national states that would completely do away with the system of historic regions based on the old feudal system. At the 1848 Slavic Congress in Prague, the Slovenian delegates also demanded the establishment of the Slovenian University in Ljubljana. A map of a United Slovenia was designed by Peter Kozler based on then available ethnic data. It was confiscated by Austrian authorities, and Kozler was accused of treason in 1852 but was later released for insufficient evidence. The revolts of 1848 were repressed after a few years, and absolutistic regimes kept control on any movements in support of national rights. However, recognition was given to equal rights of the Slovenian language in principle, while denied in practice by the German/Hungarian element that considered Slovenian the language of servants and peasants. Even the "minimalist" Maribor program of 1865 (a common assembly of deputies from the historical provinces to discuss mutual problems) was fiercely opposed by most Austrians that supported the Pan-German plan of a unified German nation from the Baltic to the Adriatic seas. The Slovenian nation was blocking the Pan-German plan simply by being located between the Adriatic Sea (Trieste) and the German/Austrian Alpine areas; therefore, any concessions had to be refused in order to speed up its total assimilation. Hitler's World War II plan to "cleanse" the Slovenians was an accelerated approach to the same end by use of extreme violence.

Toward "Yugoslavism"

In 1867, the German and Hungarian majorities agreed to the reorganization of the state into a "Dualistic" Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in order to be better able to control the minority elements in each half of the empire. The same year, in view of such intransigence, the Slovenes reverted back to their "maximalist" demand of a "United Slovenia" (1867 Ljubljana Manifesto) and initiated a series of mass political meetings, called "Tabori," after the Czech model. Their motto became "Umreti nocemo!" ("We refuse to die!"), and a movement was initiated to bring about a cultural/political coalition of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs of Austro-Hungary in order to more successfully defend themselves from the increasing efforts of Germanization/Magyarization. At the same time, Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs followed with great interest several movements of national liberation and unification, such as those in Italy, Germany, Greece, and Serbia, and drew from them much inspiration. While Austria lost its northern Italian provinces to the Italian "Risorgimento," it gained, on the other hand, Bosnia and Herzegovina through occupation (1878) and annexation (1908). These actions increased the interest of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs of Austro-Hungary in a "Trialistic" arrangement that would allow the South Slavic groups ("Yugoslavs") to form their own joint (and "Third") unit within Austro-Hungary. A federalist solution, they believed, would make possible the survival of a country to which they had been loyal subjects for many centuries. Crown Prince Ferdinand supported this approach, called "The United States of greater Austria" by his advisers, also because it would remove the attraction of a Greater Serbia. But the German leadership's sense of its own superiority and consequent expansionist goals prevented any compromise and led to two world wars.

World War I and Royal Yugoslavia

Unable to achieve their maximalist goals, the Slovenes concentrated their effort at the micro-level and made tremendous strides prior to World War I in introducing education in Slovenian, organizing literary and reading rooms in every town, participating in economic development, upgrading their agriculture, organizing cultural societies and political parties, such as the Catholic People's Party in 1892 and the Liberal Party in 1894, and participating in the Socialist movement of the 1890s. World War I brought about the dissolution of centuriesold ties between the Slovenes and the Austrian Monarchy and the Croats/Serbs with the Hungarian Crown. Toward the end of the war, on 12 August 1918, the National Council for Slovenian Lands was formed in Ljubljana. On 12 October 1918, the National Council for all Slavs of former Austro-Hungary was founded in Zagreb, Croatia, and was chaired by Msgr. Anton Korošeć, head of the Slovenian People's Party. This Council proclaimed on 29 October 1918 the separation of the South Slavs from Austro-Hungary and the formation of a new state of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs.

A National Government for Slovenia was established in Ljubljana. The Zagreb Council intended to negotiate a Federal Union with the Kingdom of Serbia that would preserve the respective national autonomies of the Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. Msgr. Korošeć had negotiated a similar agreement in Geneva with Nikola Pašić, his Serbian counterpart, but a new Serbian government reneged on it. There was no time for further negotiations due to the Italian occupation of much Slovenian and Croatian territory and only Serbia, a victor state, could resist Italy. Thus, a delegation of the Zagreb Council submitted to Serbia a declaration expressing the will to unite with The Kingdom of Serbia. At that time, there were no conditions presented or demand made regarding the type of union, and Serbia immediately accepted the proposed unification under its strongly centralized government; a unitary "Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes" was declared on 1 December 1918. Because of the absence of an initial compromise between the Unitarists and Federalists, what became Yugoslavia never gained a solid consensual foundation. Serbs were winners and viewed their expansion as liberation of their Slavic brethren from Austria-Hungary, as compensation for their tremendous war sacrifices, and as the realization of their "Greater Serbia" goal. Slovenes and Croats, while freed from the Austro-Hungarian domination, were nevertheless the losers in terms of their desired political/cultural autonomy. In addition, they suffered painful territorial losses to Italy (some 700,000 Slovenes and Croats were denied any national rights by Fascist Italy and subjected to all kinds of persecutions) and to Austria (a similar fate for some 100,000 Slovenes left within Austria in the Carinthia region).

After 10 years of a contentious parliamentary system that ended in the murder of Croatian deputies and their leader Stjepan Radić, King Alexander abrogated the 1921 constitution, dissolved the parliament and political parties, took over power directly, and renamed the country "Yugoslavia." He abolished the 33 administrative departments that had replaced the historic political/national regions in favor of administrative areas named mostly after rivers. A new policy was initiated with the goal of creating a single "Yugoslav" nation out of the three "Tribes" of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. But in practice this policy meant the King's Serbian hegemony over the rest of the nations. The reaction was intense, and King Alexander himself fell victim of Croat-Ustaša and Macedonian terrorists and died in Marseilles in 1934. A regency ruled Yugoslavia, headed by Alexander's cousin, Prince Paul, who managed to reach an agreement in 1939 with the Croats. An autonomous Croatian "Banovina" headed by "Ban" Ivan Subašić was established, including most Croatian lands outside of the Bosnia and Herzegovina area. Strong opposition developed among Serbs because they viewed the Croatian Banovina as a privilege for Croats while Serbs were split among six old administrative units with a large Serbian population left inside the Croatian Banovina itself. Still, there might have been a chance for further similar agreements that would have satisfied the Serbs and Slovenes. But there was no time left—Hitler and his allies (Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria) attacked Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941, after a coup on 27 March 1941 had deposed Prince Paul's government, which had yielded to Hitler's pressures on 25 March. Thus the first Yugoslavia, born out of the distress of World War I, had not had time to consolidate and work out its problems in a mere 23 years and was then dismembered by its aggressors. Still, the first Yugoslavia allowed the Slovenes a chance for fuller development of their cultural, economic, and political life, in greater freedom and relative independence for the first time in modern times.

World War II

Slovenia was divided in 1941 among Germany, Italy, and Hungary. Germany annexed northern Slovenia, mobilized its men into the German army, interned, expelled, or killed most of the Slovenian leaders, and removed to labor camps the populations of entire areas, repopulating them with Germans. Italy annexed southern Slovenia but did not mobilize its men. In both areas, particularly the Italian, resistance movements were initiated by both nationalist groups and by Communist-dominated Partisans, the latter particularly after Hitler's attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. The partisans claimed monopoly of the resistance leadership and dealt cruelly with anyone that dared to oppose their intended power grab. Spontaneous resistance to the Partisans by the non-Communist Slovenian peasantry led to a bloody civil war in Slovenia under foreign occupiers, who encouraged the bloodshed. The resistance movement led by General Draza Mihajlović, appointed Minister of War of the Yugoslav Government in exile, was handicapped by the exile government's lack of unity and clear purpose (mostly due to the fact that the Serbian side had reneged on the 1939 agreement on Croatia). On the other hand, Winston Churchill, convinced by rather one-sided reports that Mihajlović was "collaborating" with the Germans while the Partisans under Marshal Tito were the ones "who killed more Germans," decided to recognize Tito as the only legitimate Yugoslav resistance. Though aware of Tito's communist allegiance to Stalin, Churchill threw his support to Tito, and forced the Yugoslav government-in-exile into a coalition government with Tito, who had no intention of keeping the agreement and, in fact, would have fought against an Allied landing in Yugoslavia along with the Germans.

When Soviet armies, accompanied by Tito, entered Yugoslavia from Romania and Bulgaria in the fall of 1944, military units and civilians that had opposed the Partisans retreated to Austria or Italy. Among them were the Cetnik units of Draza Mihajlović and "homeguards" from Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia that had been under German control but were pro-Allies in their convictions and hopes. Also in retreat were the units of the Croatian Ustaša that had collaborated with Italy and Germany in order to achieve (and control) an "independent" greater Croatia and, in the process, had committed terrible and large-scale massacres of Serbs, Jews, Gypsies, and others who opposed them. Serbs and Partisans counteracted, and a fratricidal civil war raged over Yugoslavia. After the end of the war, the Communist-led forces took control of Slovenia and Yugoslavia and instituted a violent dictatorship that committed systematic crimes and human rights violations on an unexpectedly large scale. Thousands upon thousands of their former opponents that were returned, unaware, from Austria by British military authorities were tortured and massacred by Partisan executioners.

Communist Yugoslavia

Such was the background for the formation of the second Yugoslavia as a Federative People's Republic of five nations (Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Macedonians, Montenegrins) with their individual republics and Bosnia and Herzegovina as a buffer area with its mix of Serb, Muslim, and Croat populations. The problem of large Hungarian and Muslim Albanian populations in Serbia was solved by creating for them the autonomous region of Vojvodina (Hungarian minority) and Kosovo (Muslim Albanian majority) that assured their political and cultural development. Tito attempted a balancing act to satisfy most of the nationality issues that were carried over unresolved from the first Yugoslavia, but failed to satisfy anyone.

Compared to pre-1941 Yugoslavia where Serbs enjoyed a controlling role, the numerically stronger Serbs had lost both the Macedonian area they considered "Southern Serbia" and the opportunity to incorporate Montenegro into Serbia, as well as losing direct control over the Hungarian minority in Vojvodina and the Muslim Albanians of Kosovo, viewed as the cradle of the Serbian nation since the Middle Ages. They further were not able to incorporate into Serbia the large Serbian populated areas of Bosnia and had not obtained an autonomous regions for the large minority of Serbian population within the Croatian Republic. The Croats, while gaining back the Medjumurje area from Hungary and from Italy, the cities of Rijeka (Fiume), Zadar (Zara), some Dalmatian islands, and the Istrian Peninsula had, on the other hand, lost other areas. These included the Srem area to Serbia, and also Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had been part of the World War II "independent" Croatian state under the Ustaša leadership.

In addition, the Croats were confronted with a deeply resentful Serbian minority that became ever more pervasive in public administrative and security positions. The Slovenes had regained the Prekmurje enclave from Hungary and most of the Slovenian lands that had been taken over by Italy following World War I (Julian region and Northern Istria), except for the "Venetian Slovenia" area, the Gorizia area, and the port city of Trieste. The latter was initially part of the UN protected "Free Territory of Trieste," split in 1954 between Italy and Yugoslavia with Trieste itself given to Italy. Nor were the Slovenian claims to the southern Carinthia area of Austria satisfied. The loss of Trieste was a bitter pill for the Slovenes and many blamed it on the fact that Tito's Yugoslavia was, initially, Stalin's advance threat to Western Europe, thus making the Allies more supportive of Italy.

The official position of the Marxist Yugoslav regime was that national rivalries and conflicting interests would gradually diminish through their sublimation into a new Socialist order. Without capitalism, nationalism was supposed to wither away. Therefore, in the name of their "unity and brotherhood" motto, any nationalistic expression of concern was prohibited and repressed by the dictatorial and centralized regime of the "League of Yugoslav Communists" acting through the "Socialist Alliance" as its mass front organization.

After a short post-war "coalition" government period, the elections of 11 November 1945, boycotted by the noncommunist "coalition" parties, gave the Communist-led People's Front 90% of the vote. A Constituent Assembly met on 29 November, abolishing the monarchy and establishing the Federative People's Republic of Yugoslavia. In January 1946 a new constitution was adopted, based on the 1936 Soviet constitution. The Stalin-engineered expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Soviet-dominated Cominform Group in 1948 was actually a blessing for Yugoslavia after its leadership was able to survive Stalin's pressures. Survival had to be justified, both practically and in theory, by developing a "Road to Socialism" based on Yugoslavia's own circumstances. This new "road map" evolved rather quickly in response to some of Stalin's accusations and Yugoslavia's need to perform a balancing act between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance and the Soviet bloc. Tito quickly nationalized the economy through a policy of forced industrialization, to be supported by the collectivization of the agriculture.

The agricultural reform of 1945–46 (limited private ownership of a maximum of 35 hectares/85 acres, and a limited free market after the initial forced delivery of quotas to the state at very low prices) had to be abandoned because of the strong resistance by the peasants. The actual collectivization efforts were initiated in 1949 using welfare benefits and lower taxes as incentives along with direct coercion. But collectivization had to be abandoned by 1958 simply because its inefficiency and low productivity could not support the concentrated effort of industrial development.

By the 1950s Yugoslavia had initiated the development of its internal trademark: self-management of enterprises through workers councils and local decision-making as the road to Marx's "withering away of the state." The second five-year plan (1957–61), as opposed to the failed first one (1947–51), was completed in four years by relying on the well-established self-management system. Economic targets were set from the local to the republic level and then coordinated by a Federal Planning Institute to meet an overall national economic strategy. This system supported a period of very rapid industrial growth in the 1950s from a very low base. But a high consumption rate encouraged a volume of imports far in excess of exports, largely financed by foreign loans. In addition, inefficient and low productivity industries were kept in place through public subsidies, cheap credit, and other artificial measures that led to a serious crisis by 1961.

Reforms were necessary and, by 1965, "market socialism" was introduced with laws that abolished most price controls and halved import duties while withdrawing export subsidies. After necessary amounts were left with the earning enterprise, the rest of the earned foreign currencies were deposited with the national bank and used by the state, other enterprises, or were used to assist less-developed areas. Councils were given more decisionmaking power in investing their earnings, and they also tended to vote for higher salaries in order to meet steep increases in the cost of living. Unemployment grew rapidly even though "political factories" were still subsidized. The government thus relaxed its restrictions to allow labor migration, particularly to West Germany where workers were needed for its thriving economy. Foreign investment was encouraged up to 49% in joint enterprises, and barriers to the movement of people and exchange of ideas were largely removed.

The role of trade unions continued to be one of transmission of instructions from government to workers, allocation of perks along with the education/training of workers, monitoring legislation, and overall protection of the self-management system. Strikes were legally neither allowed nor forbidden, but until the 1958 miners strike in Trbovlje, Slovenia, were not publicly acknowledged and were suppressed. After 1958 strikes were tolerated as an indication of problems to be resolved. Unions, however, did not initiate strikes but were expected to convince workers to go back to work.

Having survived its expulsion from the Cominform in 1948 and Stalin's attempts to take control, Yugoslavia began to develop a foreign policy independent of the Soviet Union. By mid-1949 Yugoslavia withdrew its support from the Greek Communists in their civil war against the then-Royalist government. In October 1949, Yugoslavia was elected to one of the non-permanent seats on the UN Security Council and openly condemned North Korea's aggression towards South Korea. Following the "rapprochement" opening with the Soviet Union, initiated by Nikita Khrushchev and his 1956 denunciation of Stalin, Tito intensified his work on developing the movement of non-aligned "third world" nations as Yugoslavia's external trademark in cooperation with Nehru of India, Nasser of Egypt, and others. With the September 1961 Belgrade summit conference of non-aligned nations, Tito became the recognized leader of the movement. The non-aligned position served Tito's Yugoslavia well by allowing Tito to draw on economic and political support from the Western powers while neutralizing any aggression from the Soviet bloc. While Tito had acquiesced, reluctantly, to the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary for fear of chaos and any liberalizing impact on Yugoslavia, he condemned the Soviet invasion of Dubcek's Czechoslovakia in 1968, as did Romania's Ceausescu, both fearing their countries might be the next in line for "corrective" action by the Red Army and the Warsaw Pact. Just before his death on 4 May 1980, Tito also condemned the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Yugoslavia actively participated in the 1975 Helsinki Conference and agreements and the first 1977–78 review conference that took place in Belgrade, even though Yugoslavia's one-party Communist regime perpetrated and condoned numerous human rights violations. Overall, in the 1970s–80s Yugoslavia maintained fairly good relations with its neighboring states by playing down or solving pending disputes such as the Trieste issue with Italy in 1975, and developing cooperative projects and increased trade.

Compared to the other republics of the Federative People's Republic of Yugoslavia, the Republic of Slovenia had several advantages. It was 95% homogeneous. The Slovenes had the highest level of literacy. Their pre-war economy was the most advanced and so was their agriculture, which was based on an extensive network of peasant cooperatives and savings and loans institutions developed as a primary initiative of the Slovenian People's Party ("clerical"). Though ravaged by the war, occupation, resistance and civil war losses, and preoccupied with carrying out the elimination of all actual and potential opposition, the Communist government faced the double task of building its Socialist economy while rebuilding the country. As an integral part of the Yugoslav federation, Slovenia was, naturally, affected by Yugoslavia's internal and external political developments. The main problems facing communist Yugoslavia/Slovenia were essentially the same as the unresolved ones under Royalist Yugoslavia. As the "Royal Yugoslavism" had failed in its assimilative efforts, so did the "Socialist Yugoslavism" fail to overcome the forces of nationalism. In the case of Slovenia there were several key factors in the continued attraction to its national identity: more than a thousand years of historical development; a location within Central Europe (not part of the Balkan area) and related identification with Western European civilization; the Catholic religion with the traditional role of Catholic priests (even under the persecutions by the Communist regime); the most developed and productive economy with a standard of living far superior to most other areas of the Yugoslav Federation; and finally, the increased political and economic autonomy enjoyed by the Republic after the 1974 constitution, particularly following Tito's death in 1980. Tito's motto of "unity and brotherhood" was replaced by "freedom and democracy" to be achieved through either a confederative rearrangement of Yugoslavia or by complete independence.

In December 1964, the eighth Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (LCY) acknowledged that ethnic prejudice and antagonisms existed in socialist Yugoslavia and went on record against the position that Yugoslavia's nations had become obsolete and were disintegrating into a socialist "Yugoslavism." Thus the republics, based on individual nations, became bastions of a strong Federalism that advocated the devolution and decentralization of authority from the federal to the republic level. "Yugoslav Socialist Patriotism" was at times defined as a deep feeling for both one's own national identity and for the socialist self-management of Yugoslavia. Economic reforms were the other focus of the Eighth LCY Congress, led by Croatia and Slovenia with emphasis on efficiencies and local economic development decisions with profit criteria as their basis. The "liberal" bloc (Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia, Vojvodina) prevailed over the "conservative" group and the reforms of 1965 did away with central investment planning and "political factories." The positions of the two blocs hardened into a national-liberal coalition that viewed the conservative, centralist group led by Serbia as the "Greater Serbian" attempt at majority domination. The devolution of power in economic decision-making spearheaded by the Slovenes assisted in the "federalization" of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia as a league of "quasi-sovereign" republican parties. Under strong prodding from the Croats, the party agreed in 1970 to the principle of unanimity for decision-making that, in practice, meant a veto power for each republic. However, the concentration of economic resources in Serbian hands continued with Belgrade banks controlling half of total credits and some 80% of foreign credits. This was also combined with the fear of Serbian political and cultural domination, particularly with respect to Croatian language sensitivities, which had been aroused by the use of the Serbian version of Serbo-Croatian as the norm, with the Croatian version as a deviation. The debates over the reforms of the 1960s led to a closer scrutiny, not only of the economic system, but also of the decision-making process at the republic and federal levels, particularly the investment of funds to less developed areas that Slovenia and Croatia felt were very poorly managed, if not squandered. Other issues fueled acrimony between individual nations, such as the 1967 Declaration in Zagreb claiming a Croatian linguistic and literary tradition separate from the Serbian one, thus undermining the validity of the Serbo-Croatian language. Also, Kosovo Albanians and Montenegrins, along with Slovenes and Croats, began to assert their national rights as superior to the Federation ones.

The language controversy exacerbated the economic and political tensions between Serbs and Croats, which spilled into the easily inflamed area of ethnic confrontations. To the conservative centralists the devolution of power to the republic level meant the subordination of the broad "Yugoslav" and "Socialist" interests to the narrow "nationalist" interest of republic national majorities. With the Croat League of Communists taking the liberal position in 1970, nationalism was rehabilitated. Thus the "Croatian Spring" bloomed and impacted all the other republics of Yugoslavia. Meanwhile, through a series of 1967–68 constitutional amendments that had limited federal power in favor of the republics and autonomous provinces, the Federal Government came to be seen by liberals more as an inter-republican problem-solving mechanism bordering on a confederative arrangement. A network of inter-republican committees established by mid-1971 proved to be very efficient at resolving a large number of difficult issues in a short time. The coalition of liberals and nationalists in Croatia also generated sharp condemnation in Serbia whose own brand of nationalism grew stronger, but as part of a conservative/centralist alliance. Thus the liberal/federalist versus conservative/centralist opposition became entangled in the rising nationalism within each opposing bloc. The situation in Croatia and Serbia was particularly difficult because of their minorities issues—Serbian in Croatia and Hungarian/Albanian in Serbia.

Serbs in Croatia sided with the Croat conservatives and sought a constitutional amendment guaranteeing their own national identity and rights and, in the process, challenged the sovereignty of the Croatian nation and state as well as the right to self-determination, including the right to secession. The conservatives won and the amendment declared that "the Socialist Republic of Croatia (was) the national state of the Croatian nation, the state of the Serbian nation in Croatia, and the state of the nationalities inhabiting it."

Slovenian "Spring"

Meanwhile, Slovenia, not burdened by large minorities, developed a similar liberal and nationalist direction along with Croatia. This fostered an incipient separatist sentiment opposed by both the liberal and conservative party wings. Led by Stane Kavcic, head of the Slovenian government, the liberal wing gained as much local political latitude as possible from the Federal level during the early 1970s "Slovenian Spring." By the summer of 1971, the Serbian party leadership was pressuring President Tito to put an end to the "dangerous" development of Croatian nationalism. While Tito wavered because of his support for the balancing system of autonomous republic units, the situation quickly reached critical proportions.

Croat nationalists, complaining about discrimination against Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, demanded the incorporation of Western Herzegovina into Croatia. Serbia countered by claiming Southeastern Herzegovina for itself. Croats also advanced claims to a larger share of their foreign currency earnings, to the issuance of their own currency, the creation of their own national bank that would directly negotiate foreign loans, the printing of Croatian postage stamps, the creation of a Croatian army, and recognition of the Croatian Sabor (assembly) as the highest Croatian political body, and, finally, to Croatian secession and complete independence. Confronted with such intensive agitation, the liberal Croatian party leadership could not back down and did not try to restrain the maximalist public demands nor the widespread university students' strike of November 1971. This situation caused a loss of support from the liberal party wings of Slovenia and even Macedonia. At this point Tito intervened, condemned the Croatian liberal leadership on 1 December 1971, and supported the conservative wing. The liberal leadership group resigned on 12 December 1971. When Croatian students demonstrated and demanded an independent Croatia, the Yugoslav army was ready to move in if necessary. A wholesale purge of the party liberals followed with tens of thousands expelled, key functionaries lost their positions, several thousand were imprisoned (including Franjo Tudjman who later became President in independent Croatia), and leading Croatian nationalist organizations and their publications were closed.

On 8 May 1972, the Croatian party also expelled its liberal wing leaders and the purge of nationalists continued through 1973 in Croatia, as well as in Slovenia and Macedonia. However, the issues and sentiments raised during the "Slovene and Croat Springs" of 1969–71 did not disappear. Tito and the conservatives were forced to satisfy nominally some demands. The 1974 constitution was an attempt to resolve the strained inter-republican relations as each republic pursued its own interests over and above an overall "Yugoslav" interest. The repression of liberal-nationalist Croats was accompanied by the growing influence of the Serbian element in the Croatian Party (24% in 1980) and police force (majority) that contributed to the continued persecution and imprisonments of Croatian nationalists into the 1980s.

Yugoslavia—House Divided

In Slovenia, developments took a direction of their own. The purge of the nationalists took place as in Croatia but on a lesser scale, and after a decade or so, nationalism was revived through the development of grassroots movements in the arts, music, peace, and environmental concerns. Activism was particularly strong among young people, who shrewdly used the regime-supported youth organizations, youth periodicals—such as Mladina (in Ljubljana) and Katedra (in Maribor)—and an independent student radio station. The journal Nova Revija published a series of articles focusing on problems confronting the Slovenian nation in February 1987; these included such varied topics as the status of the Slovenian language, the role of the Communist Party, the multi-party system, and independence. The Nova Revija was in reality a Slovenian national manifesto that, along with yearly public opinion polls showing ever higher support for Slovenian independence, indicated a definite mood toward secession. In this charged atmosphere, the Yugoslav army committed two actions that led the Slovenes to the path of actual separation from Yugoslavia. In March 1988, the army's Military Council submitted a confidential report to the Federal Presidency claiming that Slovenia was planning a counter revolution and calling for repressive measures against liberals and a coup d'etat. An army document delineating such actions was delivered by an army sergeant to the journal Mladina. But, before it could be published, Mladina's editor and two journalists were arrested by the army on 31 March 1988. Meanwhile, the strong intervention of the Slovenian political leadership succeeded in stopping any army action. But the four men involved in the affair were put on trial by the Yugoslav army.

The second army faux pas was to hold the trial in Ljubljana, capital of Slovenia, and to conduct it in the Serbo-Croatian language, an action declared constitutional by the Yugoslav Presidency, claiming that Slovenian law could not be applied to the Yugoslav army. This trial brought about complete unity among Slovenians in opposition to the Yugoslav army and what it represented, and the four individuals on trial became overnight heroes. One of them was Janez Janša who had written articles in Mladina critical of the Yugoslav army and was the head of the Slovenian pacifist movement and President of the Slovenian Youth Organization. (Ironically, three years later Janša led the successful defense of Slovenia against the Yugoslav army and became the first Minister of Defense of independent Slovenia.) The four men were found guilty and sentenced to jail terms from four years (Janša) to five months. The total mobilization of Slovenia against the military trials led to the formation of the first non-Communist political organizations and political parties. In a time of perceived national crisis, both the Communist and non-Communist leadership found it possible to work closely together. But from that time on the liberal/nationalist vs. conservative/centralist positions hardened in Yugoslavia and no amount of negotiation at the federal presidency level regarding a possible confederal solution could hold Yugoslavia together any longer.

Since 1986, work had been done on amendments to the 1974 constitution that, when submitted in 1987, created a furor, particularly in Slovenia, due to the proposed creation of a unified legal system, the establishment of central control over the means of transportation and communication, centralization of the economy into a unified market, and the granting of more control to Serbia over its autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. This all came at the expense of the individual republics. A recentralization of the League of Communists was also recommended but opposed by liberal/nationalist groups. Serbia's President Slobodan Milošević also proposed changes to the bicameral Federal Skupština (Assembly) by replacing it with a tricameral one where deputies would no longer be elected by their republican assemblies but through a "one person, one vote" national system. Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina strongly opposed the change as they opposed the additional Chamber of Associated Labor that would have increased the Federal role in the economy. The debates over the recentralizing amendments caused an even greater focus in Slovenia and Croatia on the concept of a confederative structure based on self-determination by "sovereign" states and a multiparty democratic system as the only one that could maintain some semblance of a "Yugoslav" state.

By 1989 and the period following the Serbian assertion of control in the Kosovo and Vojvodina provinces, as well as in the republic of Montenegro, relations between Slovenia and Serbia reached a crisis point: Serbian President Milošević attempted to orchestrate mass demonstrations by Serbs in Ljubljana, the capital city of Slovenia, and the Slovenian leadership vetoed it. Then Serbs started to boycott Slovenian products, to withdraw their savings from Slovenian banks, and to terminate economic cooperation and trade with Slovenia. Serbian President Milošević's tactics were extremely distasteful to the Slovenians and the use of force against the Albanian population of the Kosovo province worried the Slovenes (and Croats) about the possible use of force by Serbia against Slovenia itself. The tensions with Serbia convinced the Slovenian leadership of the need to take necessary protective measures. In September 1989, draft amendments to the constitution of Slovenia were published that included the right to secession, and the sole right of the Slovenian legislature to introduce martial law. The Yugoslav army particularly needed the amendment granting control over deployment of armed forces in Slovenia, since the Yugoslav army, controlled by a mostly Serbian/Montenegrin officer corps dedicated to the preservation of a communist system, had a self-interest in preserving the source of their own budgetary allocations of some 51% of the Yugoslav federal budget.

A last attempt at salvaging Yugoslavia was to be made as the extraordinary Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia convened in January 1990 to review proposed reforms such as free multi-party elections, and freedom of speech. The Slovenian delegation attempted to broaden the spectrum of reforms but was rebuffed and walked out on 23 January 1990, pulling out of the Yugoslav League. The Slovenian Communists then renamed their party the Party for Democratic Renewal. The political debate in Slovenia intensified and some nineteen parties were formed by early 1990. On 10 April 1990 the first free elections since before World War II were held in Slovenia, where there still was a three-chamber Assembly: political affairs, associated labor, and territorial communities. A coalition of six newly formed democratic parties, called Demos, won 55% of the votes, with the remainder going to the Party for Democratic Renewal, the former Communists (17%), the Socialist Party (5%), and the Liberal Democratic Party—heir to the Slovenia Youth Organization (15%). The Demos coalition organized the first freely elected Slovenian government of the post-Communist era with Dr. Lojze Peterle as the prime minister.

Milan Kucan, former head of the League of Communists of Slovenia, was elected president with 54% of the vote in recognition of his efforts to effect a bloodless transfer of power from a monopoly by the Communist party to a free multi-party system and his standing up to the recentralizing attempts by Serbia.

Toward Independence

In October 1990, Slovenia and Croatia published a joint proposal for a Yugoslavian confederation as a last attempt at a negotiated solution, but to no avail. The Slovenian legislature also adopted in October a draft constitution proclaiming that "Slovenia will become an independent state." On 23 December 1990, a plebiscite was held on Slovenia's disassociation from Yugoslavia if a confederate solution could not be negotiated within a six-month period. An overwhelming majority of 89% of voters approved the secession provision and a declaration of sovereignty was adopted on 26 December 1990. All federal laws were declared void in Slovenia as of 20 February 1991, and since no negotiated agreement was possible, Slovenia declared its independence on 25 June 1991. On 27 June 1991, the Yugoslav army tried to seize control of Slovenia and its common borders with Italy, Austria, and Hungary under the pretext that it was the army's constitutional duty to assure the integrity of Socialist Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav army units were surprised and shocked by the resistance they encountered from the Slovenian "territorial guards," who surrounded Yugoslav Army tank units, isolated them, and engaged in close combat, mostly along border checkpoints that ended in most cases with Yugoslav units surrendering to the Slovenian forces. Fortunately, casualties were limited on both sides. Over 3,200 Yugoslav army soldiers surrendered and were well treated by the Slovenes, who scored a public relations coup by having the prisoners call their parents all over Yugoslavia to come to Slovenia and take their sons back home.

The war in Slovenia ended in 10 days due to the intervention of the European Community, who negotiated a cease-fire and a three-month moratorium on Slovenia's implementation of independence, giving the Yugoslav army time to retreat from Slovenia by the end of October 1991. Thus Slovenia was able to "disassociate" itself from Yugoslavia with a minimum of casualties, although the military operations caused considerable physical damages estimated at almost US $3 billion. On 23 December 1991, one year following the independence plebiscite, a new constitution was adopted by Slovenia establishing a parliamentary democracy with a bicameral legislature. Even though US Secretary of State James Baker, in his visit to Belgrade on 21 June 1991, had declared that the US opposed unilateral secessions by Slovenia and Croatia and that the US would therefore not recognize them as independent countries, such recognition came first from Germany on 18 December 1991, from the European Community on 15 January 1992, and finally from the US on 7 April 1992. Slovenia was accepted as a member of the UN on 23 April 1992 and has since become a member of many other international organizations, including the Council of Europe in 1993 and the NATO related Partnership for Peace in 1994.

On 6 December 1992, general elections were held in accordance with the new constitution, with 22 parties participating and eight receiving sufficient votes to assure representation. A coalition government was formed by the Liberal Democrats, Christian Democrats, and the United List Group of Leftist Parties. Dr. Milan Kucan was elected president, and Dr. Janez Drnovšek became prime minister. In 1997 a compromise was struck which allowed Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary to join the NATO alliance in 1999 while Romania and Slovenia were identified as prime candidates for future nomination into the alliance. Also in 1997, Slovenia signed an association agreement with the European Union (EU) and was invited to talks on EU membership.

In the 1970s, Slovenia had reached a standard of living close to the one in neighboring Austria and Italy. However, the burdens imposed by the excessive cost of maintaining a large Yugoslav army, heavy contributions to the Fund for Less Developed Areas, and the repayments on a US $20 billion international debt, caused a lowering of its living standard over the 1980s. The situation worsened with the trauma of secession from Yugoslavia, the war damages suffered, and the loss of the former Yugoslav markets. In spite of all these problems Slovenia has made progress since independence by improving its productivity, controlling inflation, and reorienting its exports to Western Europe. The Slovenian economy has been quite strong since 1994, growing at an annual rate of about 4% during the late 1990s. Based on past experience, its industriousness, and good relationship with its trading partners, Slovenia has a very good chance of becoming a successful example of the transition from authoritarian socialism to a free democratic system and a market economy capable of sustaining a comfortable standard and quality of life.

Although governed from independence by centrist coalitions headed by Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek, the coalition collapsed in April 2000. Economist and center-right Social Democrat Party leader Andrej Bajuk became prime minister, until elections on 15 October 2000 saw Drnovšek return to power at the head of a four-party coalition. Drnovšek ran for president in elections held on 1 December 2002, and emerged with 56.5% of the vote in the second round, defeating Barbara Brezigar, who took 43.5%. Both supported EU and NATO membership for Slovenia. Liberal Democrat Anton Rop took over as prime minister when Drnovšek was elected president. At a NATO summit held in Prague that November, Slovenia was one of seven countries officially invited to join the organization, and in December at an EU summit in Copenhagen, Slovenia was invited to join that body in 2004. On 23 March 2003, Slovenians approved both NATO and EU membership in referendums. The vote in favor of the EU was over 89%, and that for NATO was 66%. Turnout was 60%.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: