Macedonia - History

Origin and Middle Ages

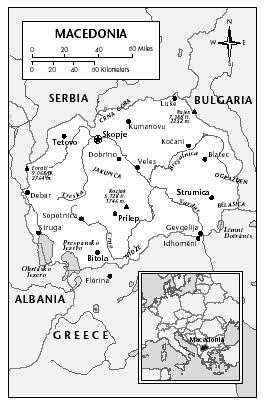

Macedonia is an ancient name, historically related to Philip II of Macedon, whose son became Alexander the Great, founder of one of the great empires of the ancient world. As a regional name, Macedonia, the land of the Macedons, has been used since ancient Greek times for the territory extending north of Thessaly and into the Vardar River Valley and between Epirus on the west and Thrace on the east. In Alexander the Great's time, Macedonia extended west to the Adriatic Sea over the area then called Illyris, part of today's Albania. Under the Roman Empire, Macedonia was extended south over Thessaly and Achaia.

Beginning in the 5th century AD Slavic tribes began settling in the Balkan area, and by 700 they controlled most of the Central and Peloponnesian Greek lands. The Slavic conquerors were mostly assimilated into Greek culture except in the northern Greek area of Macedonia proper and the areas of northern Thrace populated by "Bulgarian" Slavs. That is how St. Cyril and Methodius, two Greek brothers and scholars who grew up in the Macedonian city of Salonika, were able to become the "Apostles of the Slavs," having first translated Holy Scriptures in 863 into the common Slavic language they had learned in the Macedonian area.

Through most of the later Middle Ages, Macedonia was an area contested by the Byzantine Empire, with its Greek culture and Orthodox Christianity, the Bulgarian Kingdom, and particularly the 14th century Serbian empire of Dušan the Great. The Bulgarian and Serbian empires contributed to the spread of Christianity through the establishment of the Old Church Slavic liturgy.

After Dušan's death in 1355 his empire collapsed, partly due to the struggle for power among his heirs and partly to the advances of the Ottoman Turks. Following the defeat of the Serbs at the Kosovo Field in 1389, the Turks conquered the Macedonian area over the next half century and kept it under their control until the 1912 Balkan war.

Under Ottoman Rule

The decline of the Ottoman Empire brought about renewed competition over Slavic Macedonia between Bulgaria and Serbia. After the Russo-Turkish war of 1877 ended in a Turkish defeat, Bulgaria, an ally of Russia, was denied the prize of the Treaty of San Stefano (1878) in which Turkey had agreed to an enlarged and autonomous Bulgaria that would have included most of Macedonia. Such an enlarged Bulgaria—with control of the Vardar River Valley and access to the Aegean Sea—was, however, a violation of a prior Russo-Austrian agreement. The Western powers opposed Russia's penetration into the Mediterranean through the port of Salonika and, at the 1878 Congress of Berlin, forced the "return" of Macedonia and East Rumelia from Bulgaria to Turkey. This action enraged Serbia, which had fought in the war against Turkey, gained its own independence, and hoped to win control of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which had been given over to Austrian control, for itself.

In this situation both Serbia and Bulgaria concentrated their efforts on Macedonia, where Greek influence had been very strong through the Greek Orthodox Church. The Bulgarians obtained their own Orthodox Church in 1870, that extended its influence to the Macedonian area and worked in favor of unification with Bulgaria through intensive educational activities designed to "Bulgarize" the Slavic population. Systematic intimidation was also used, when the Bulgarians sent their terrorist units ("Komite") into the area. The Serbian side considered Macedonia to be Southern Serbia, with its own dialect but using Serbian as its literary language. Serbian schools predated Bulgarian ones in Macedonia and continued with their work.

While individual instances of Macedonian consciousness and language had appeared by the end of the 18th century, it was in the 1850s that "Macedonists" had declared Macedonia a separate Slavic nation. Macedonian Slavs had developed a preference for their central Macedonian dialect and had begun publishing some writings in it rather than using the Bulgaro-Macedonian version promoted by the Bulgarian Church and government emissaries. Thus, Macedonia, in the second half of the 19th century, while still under the weakening rule of the Turks, had become the object of territorial and cultural claims by its Greek, Serb, and Bulgarian neighbors. The most systematic pressure had come from Bulgaria and had caused large numbers of "Bulgaro-Macedonians" to emigrate to Bulgaria—some 100,000 in the 1890s—mainly to Sophia, where they constituted almost half the city's population and an extremely strong pressure group.

Struggle for Autonomy

More and more Macedonians became convinced that Macedonia should achieve at least an autonomous status under Turkey, if not complete independence. In 1893, a secret organization was formed in Salonika aiming at a revolt against the Turks and the establishment of an autonomous Macedonia. The organization was to be independent of Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece and was named the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), a group that became Socialist, revolutionary, and terrorist in nature. Much like Ireland's IRA, IMRO spread through Macedonia and became an underground paragovernmental network active up to World War II. A pro-Bulgarian and an independent Macedonian faction soon developed, the first based in Sophia, the second in Salonika. Its strong base in Sophia gave the pro-Bulgarian faction a great advantage and it took control and pushed for an early uprising in order to impress the Western powers into intervening in support of Macedonia.

The large scale uprising took place on 2 August 1903 (Ilinden– "St. Elijah's Day") when the rebels took over the town of Kruševo and proclaimed a Socialist Republic. After initial defeats of the local Turkish forces, the rebels were subdued by massive Ottoman attacks using scorched earth tactics and wholesale massacres of the population over a three-month period. Europe and the United States paid attention and forced Turkey into granting reforms to be supervised by international observers. However, the disillusioned IMRO leadership engaged in factional bloody feuds that weakened the IMRO organization and image. This encouraged both Serbs and Greeks in the use of their own armed bands—Serbian "Cetniks" and Greek "Andarte"— creating an atmosphere of gang warfare in which Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece fought each other (instead of the Turks) over a future division of Macedonia. In the meantime, the Young Turks movement had spread among Turkish officers and military uprisings began in Macedonia in 1906. These uprisings spread and Turkish officers demanded a constitutional system. They believed that Turkey could be saved only by Westernizing. In 1908 the Young Turks prevailed, and offered to the IMRO leadership agrarian reforms, regional autonomy, and introduction of the Macedonian language in the schools. However, the Young Turks turned out to be extreme Turkish nationalists bent on the assimilation of other national groups. Their denationalizing efforts caused further rebellions and massacres in the Balkans. Serbia, Greece, Bulgaria, and Montenegro turned for help to the great powers, but to no avail. In 1912 they formed the Balkan League, provisionally agreed on the division of Turkish Balkan territory among themselves, and declared war on Turkey in October 1912 after Turkey refused their request to establish the four autonomous regions of Macedonia—Old Serbia, Epirus, and Albania—already provided for in the 1878 Treaty of Berlin.

Balkan Wars

The quick defeat of the Turks by the Balkan League stunned the European powers, particularly when Bulgarian forces reached the suburbs of Istanbul. Turkey signed a treaty in London on 30 May 1913 giving up all European possessions with the exception of Istanbul. However, when Italy and Austria vetoed a provision granting Serbia access to the Adriatic at Durazzo and Alessio and agreed to form an independent Albania, Serbia demanded a larger part of Macedonia from Bulgaria. Bulgaria refused and attacked both Serbian and Greek forces. This caused the second Balkan War that ended in a month with Bulgaria's defeat by Serbia and Greece with help from Romania, Montenegro, and Turkey. The outcome was the partitioning of Macedonia between Serbia and Greece. Turkey regained the Adrianople area it had lost to Bulgaria. Romania gained a part of Bulgarian Dobrudja while Bulgaria kept a part of Thrace and the Macedonian town of

Strumica. Thus Southern Macedonia came under the Hellenizing influence of Greece while most of Macedonia was annexed to Serbia. Both Serbia and Greece denied any Macedonian "nationhood." In Greece, Macedonians were treated as "slavophone" Greeks while Serbs viewed Macedonia as Southern Serbia and Serbian was made the official language of government and instruction in schools and churches.

First and Second Yugoslavia

After World War I, the IMRO organization became a terrorist group operating out of Bulgaria with a nuisance role against Yugoslavia. In later years, some IMRO members joined the Communist Party and tried to work toward a Balkan Federation where Macedonia would be an autonomous member. Its interest in the dissolution of the first Yugoslavia led IMRO members to join with the Croatian Ustaša in the assassination of King Alexander of Yugoslavia and French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou in Marseilles on 9 October 1934. During World War II, Bulgaria, Hitler's ally, occupied the central and eastern parts of Macedonia while Albanians, supported by Italy, annexed western Macedonia along with the Kosovo region. Because of Bulgarian control, resistance was slow to develop in Macedonia; a conflict between the Bulgarian and Yugoslav Communist parties also played a part. By the summer of 1943, however, Tito, the leader of the Yugoslav Partisans, took over control of the Communist Party of Macedonia after winning its agreement to form a separate Macedonian republic as part of a Yugoslav federation. Some 120,000 Macedonian Serbs were forced to emigrate to Serbia because they had opted for Serbian citizenship. Partisan activities against the occupiers increased and, by August 1944, the Macedonian People's Republic was proclaimed with Macedonian as the official language and the goal of unifying all Macedonians was confirmed. But this goal was not achieved. However, the "Pirin" Macedonians in Bulgaria were granted their own cultural development rights in 1947, and then lost them after the Stalin-Tito split in 1948. The Bulgarian claims to Macedonia were revived from time to time after 1948.

On the Greek side, there was no support from the Greek Communist Party for the unification of Macedonian Slavs within Greece with the Yugoslav Macedonians, even though Macedonian Slavs had organized resistance units under Greek command and participated heavily in the post-war Greek Communists' insurrection. With Tito's closing the Yugoslav-Greek frontier in July 1949 and ending his assistance to the pro-Cominform Greek Communists, any chance of territorial gains from Greece had dissipated. On the Yugoslav side, Macedonia became one of the co-equal constituent republics of the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia under the Communist regime of Marshal Tito. The Macedonian language became one of the official languages of Yugoslavia, along with Slovenian and Serbo-Croatian, and the official language of the Republic of Macedonia where the Albanian and Serbo-Croatian languages were also used. Macedonian was fully developed into the literary language of Macedonians, used as the language of instruction in schools as well as the newly established Macedonian Orthodox Church. A Macedonian University was established in Skopje, the capital city, and all the usual cultural, political, social, and economic institutions were developed within the framework of the Yugoslav Socialist system of self-management. The main goals of autonomy and socialism of the old IMRO organization were fulfilled, with the exception of the unification of the "Pirin" (Bulgarian) and "Greek" Macedonian lands.

All of the republics of the former Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia share a common history between 1945 and 1991, the year of Yugoslavia's dissolution. The World War II Partisan resistance movement, controlled by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and led by Marshal Tito, won a civil war waged against nationalist groups under foreign occupation, having secured the assistance, and recognition, from both the Western powers and the Soviet Union. Aside from the reconstruction of the country and its economy, the first task facing the new regime was the establishment of its legitimacy and, at the same time, the liquidation of its internal enemies, both actual and potential. The first task was accomplished by the 11 November 1945 elections of a constitutional assembly on the basis of a single candidate list assembled by the People's Front. The list won 90% of the votes cast. The three members of the "coalition" government representing the Royal Yugoslav Government in exile had resigned earlier in frustration and did not run in the elections. The Constitutional Assembly voted against the continuation of the Monarchy and, on 31 January 1946, the new constitution of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia was promulgated. Along with state-building activities, the Yugoslav Communist regime carried out ruthless executions, massacres, and imprisonments to liquidate any potential opposition.

The Tito-Stalin conflict that erupted in 1948 was not a real surprise considering the differences the two had had about Tito's refusal to cooperate with other resistance movements against the occupiers in World War II. The expulsion of Tito from the Cominform group separated Yugoslavia from the Soviet Bloc, caused internal purges of pro-Cominform Yugoslav Communist Party members, and also nudged Yugoslavia into a failed attempt to collectivize its agriculture. Yugoslavia then developed its own brand of Marxist economy based on workers' councils and self-management of enterprises and institutions, and became the leader of the non-aligned group of nations in the international arena. Being more open to Western influences, the Yugoslav Communist regime relaxed somewhat its central controls. This allowed for the development of more liberal wings of Communist parties, particularly in Croatia and Slovenia, which agitated for the devolution of power from the federal to the individual republic level in order to better cope with the increasing differentiation between the more productive republics (Slovenia and Croatia) and the less developed areas. Also, nationalism resurfaced with tensions particularly strong between Serbs and Croats in the Croatian Republic, leading to the repression by Tito of the Croatian and Slovenian "Springs" in 1970–71.

The 1974 constitution shifted much of the decision-making power from the federal to the republics' level, turning the Yugoslav Communist Party into a kind of federation (league) of the republican parties, thus further decentralizing the political process. The autonomous provinces of Vojvodina and Kosovo were also given a quasi-sovereign status as republics, and a collective presidency was designed to take over power upon Tito's death. When Tito died in 1980, the delegates of the six republics and the two autonomous provinces represented the interests of each republic or province in the process of shifting coalitions centered on specific issues. The investment of development funds to assist the less developed areas became the burning issue around which nationalist emotions and tensions grew ever stronger, along with the forceful repression of the Albanian majority in Kosovo.

The economic crisis of the 1980s, with runaway inflation, inability to pay the debt service on over $20 billion in international loans that had accumulated during Tito's rule, and low productivity in the less-developed areas became too much of a burden for Slovenia and Croatia, leading them to stand up to the centralizing power of the Serbian (and other) Republics. The demand for a reorganization of the Yugoslav Federation into a confederation of sovereign states was strongly opposed by the coalition of Serbia, Montenegro, and the Yugoslav army. The pressure towards political pluralism and a market economy also grew stronger, leading to the formation of non-Communist political parties that, by 1990, were able to win majorities in multi-party elections in Slovenia and then in Croatia, thus putting an end to the era of the Communist Party monopoly of power. The inability of the opposing groups of centralist and confederalist republics to find any common ground led to the dissolution of Yugoslavia through the disassociation of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Macedonia, leaving only Serbia and Montenegro together in a new Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

The years between 1945 and 1990 offered the Macedonians an opportunity for development in some areas, in addition to their cultural and nation-building efforts, within the framework of a one-party Communist system. For the first time in their history the Macedonians had their own republic and government with a very broad range of responsibilities. Forty-five years was a long enough period to have trained generations for public service responsibilities and the governing of an independent state. In addition, Macedonia derived considerable benefits from the Yugoslav framework in terms of federal support for underdeveloped areas (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro). Macedonia's share of the special development funds ranged from 26% in 1966 to about 20% in 1985, much of it supplied by Croatia and Slovenia.

In the wake of developments in Slovenia and Croatia, Macedonia held its first multi-party elections in November– December 1990, with the participation of over 20 political parties. Four parties formed a coalition government that left the strongest nationalist party (IMRO) in the opposition. In January 1991 the Macedonian Assembly passed a declaration of sovereignty.

Independence

While early in 1989 Macedonia supported Serbia's Slobodan Milošević in his recentralizing efforts, by 1991, Milošević was viewed as a threat to Macedonia and its leadership took positions closer to the confederal ones of Slovenia and Croatia. A last effort to avoid Yugoslavia's disintegration was made 3 June 1991 through a joint proposal by Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, offering to form a "community of Yugoslav Republics" with a centrally administered common market, foreign policy, and national defense. However, Serbia opposed the proposal.

On 26 June 1991—one day after Slovenia and Croatia had declared their independence—the Macedonian Assembly debated the issue of secession from Yugoslavia with the IMRO group urging an immediate proclamation of independence. Other parties were more restrained, a position echoed by Macedonian president Kiro Gligorov in his cautious statement that Macedonia would remain faithful to Yugoslavia. Yet by 6 July 1991, the Macedonian Assembly decided in favor of Macedonia's independence if a confederal solution could not be attained.

Thus, when the process of dissolution of Yugoslavia took place in 1990–91, Macedonia refused to join Serbia and Montenegro and opted for independence on 20 November 1991. The unification issue was then raised again, albeit negatively, by the refusal of Greece to recognize the newly independent Macedonia for fear that its very name would incite irredentist designs toward the Slav Macedonians in northern Greece. The issue of recognition became a problem between Greece and its NATO allies in spite of the fact that Macedonia had adopted in 1992 a constitutional amendment forbidding any engagement in territorial expansion or interference in the internal affairs of another country. In April 1993, Macedonia gained membership in the UN, but only under the name of "Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia." Greece also voted against Macedonian membership in the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe on 1 December 1993. However, on 16 December 1993, the United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands had announced the initiation of the recognition process for Macedonia and other countries joined the process, which resulted in recognition of Macedonia by the United States on 8 February 1994. In April 1994 the EU began to take legal action in the European Court of Justice against Greece for refusing to lift a trade blockade against Macedonia that it initiated two months earlier. However, by October 1995, Greece agreed to lift the embargo, in return for concessions from Macedonia that included changing its national flag, which contained an ancient Greek emblem depicting the 16-pointed golden sun of Vergina. The dispute over the name of Macedonia remained, but the agreement defused the threat of violence in the region.

On 3 October 1995, Macedonian president Kiro Gligorov narrowly survived a car-bomb attack that killed his driver. The next day, parliament named its speaker, Stojan Andov, as the interim president after determining that Gligorov was incapable of performing his functions. Gligorov resumed his duties in early 1996. As tensions between majority Albanians and minority Serbs in the neighboring Yugoslav province of Kosovo heated up from 1997 to 1999, fears mounted that full-scale fighting would spread to Macedonia. Ethnic violence erupted in the town of Gostivar in July 1997 after the Macedonian government sent in special military forces to remove the illegal Albanian, Turkish, and Macedonian flags flying outside the town hall. Several thousand protesters, some armed, had gathered and were in a stalemate with police. During the skirmish, police killed three ethnic Albanians and several policemen were shot. The Albanian nationalist Kosovo Liberation Army also claimed attacks against two police stations in Macedonia in December 1997 and January 1998. As the violence mounted the United Nations Security Council voted unanimously on 21 July 1998 to renew the UNPREDEP (United Nations Preventive Deployment Force) mandate another six months and to bolster the contingent with 350 more soldiers.

When full-scale fighting in Kosovo erupted in early 1999 and NATO responded with air strikes against Serbia, Macedonia became the destination for tens of thousands of Kosovar Albanian refugees fleeing from Serbian ethnic cleansing. For a while the situation in Macedonia remained tense as the government, fearful of a spillover of the fighting into its territory, closed its frontiers to refugees. Nonetheless, the presence of NATO forces and pledges of international aid prevented (aside from errant bombs and a couple of cross-border incursions) a spread of the fighting and maintained domestic stability in Macedonia.

However, in 2000, violence on the border with Kosovo increased, putting Macedonian troops in a state of high alert. In February 2001, fighting broke out between government forces and ethnic Albanian rebels, many from the Kosovo Liberation Army, but also ethnic Albanians from within Macedonia. The insurrection broke out in the northwest, where rebels took up arms around the town of Tetovo, where ethnic Albanians make up a majority of the population. NATO depolyed additional forces along the border with Kosovo to stop the supply of arms to the rebels; however, the buffer zone proved ineffective. As fighting intensified in March, the government closed the border with Kosovo. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 22,000 ethnic Albanians had fled the fighting by that time. Fears in Macedonia of the creation of a "Greater Albania," including Kosovo and parts of Macedonia, were fueled by the separatist movement, and mass demonstrations were held in Skopje urging tougher action against the rebels. The violence continued throughout the summer, until August, when the Ohrid Framework Agreement was signed by the government and ethnic Albanian representatives, granting greater recognition of ethnic Albanian rights in exchange for the rebels' pledge to turn over weapons to the NATO peacekeeping force.

In November 2001, parliament amended the constitution to include reforms laid out in the Ohrid Framework Agreement. The constitution recognizes Albanian as an official language, and increases access for ethnic Albanians to pubic-sector jobs, including the police. It also gives ethnic Albanians a voice in parliament, and guarantees their political, religious and cultural rights. In March 2002, parliament granted an amnesty to the former rebels who turned over their weapons to the NATO peacekeepers in August and September 2001. By September 2002, most of the 170,000 people who had fled their homes in advance of the fighting in 2001 had returned.

Parliamentary elections were held on 15 September 2002, which saw a change in leadership from the nationalist VMRODPMNE party of Prime Minister Ljubco Georgievski to the moderate Social Democratic League of Macedonia (SDSM)-led "Together for Macedonia" coalition. Branco Crvenkovski became prime minister. At that time Boris Trajkovski was president; he had been elected from the VMRO-DPMNE party in 1999. In the September 2002 elections, former ethnic Albanian rebel-turned-politician Ali Ahmeti saw his Democratic Union for Integration party (DUI) claim victory for the Albanian community, which makes up more than 25% of the Macedonian population. Ahmeti, former political leader of the National Liberation Army (NLA), delayed taking his seat in parliament until December, for fear it would ignite protests among Macedonians who still regarded him as a terrorist. Indeed, in January 2003, the DUI headquarters in Skopje came under assault from machine-gunfire and a grenade, the fourth such attack on DUI offices.

In November 2002, NATO announced that of 10 countries aspiring to join the organization, 7 would accede in 2004, leaving Albania, Macedonia, and Croatia to wait until a later round of expansion. In January 2003, Albania and Macedonia agreed to intensify bilateral cooperation, especially in the economic sphere, so as to prepare their way for NATO and EU membership.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: